Professor Alexander Kitroeff’s much anticipated book, The Greeks and the Making of Modern Egypt was released this spring, and I, like many, looked forward to reading it.

I spent the spring of 2019 teaching at the American University in Cairo (AUC) in the Graduate School of Education. During one of my classes, which covers educational systems borrowing from around the world or how many nations borrow from other nations, one student commented that Egypt was colonized for much of its history by the West, which imposed its system of education, and because of this, Egyptians don’t know who they are.

While the response was loaded, it was a good starting point for a discussion on education in Egypt and Egyptian identity.

The conversation was going well and then one student commented that because of Western influences Egyptians were losing their sense of Arab and Muslim identity. I could tell this comment made some of the students in the class uncomfortable. I quickly shifted the conversation to Egyptian history. I wanted my students to give me a straightforward and easy chronology of Egyptian history.

Students began to raise their hands while I called on them and wrote on the white-board. I said, “O.K. great! There were ancient Egyptians. Ancient Egyptian history is divided into several historical periods. What’s next? Good! The Hellenistic Period. Yes! These were the Greeks, then came the Romans. Good! What comes next? The short-lived Byzantine and Sassanid (Persian) Dynasties. Next? The Arab and Ottoman conquest. Perfect! Yup! Napoleon then Muhammed Ali’s Dynasty (Muhammed Ali happened to be Albanian) and then Modern Egypt and the rise of Pan-Arabism. Good Work!”

Much of Egypt was occupied by foreigners for much of its history, but it was not only the West, but Arabs and Muslims too.

Later that week I mentioned what had happened in my class to a colleague. She said, “Many Egyptians, especially Coptic Christians, see themselves as direct descendants of the ancient Egyptians. If anything, the Arabs and Muslims are just as much foreigners as westerners.”

It made perfect sense, imagine a white American telling a native American “We need to stop these foreigners from coming into our country, because we are losing our culture and language.”

But where are the Greek of Egypt in all this? Are they considered foreigners or colonists?

Large numbers of Greek began settling in Egypt during the Hellenistic or Ptolemaic Period (305 BC – 30 BC). There were a series of migrations of Greeks into Egypt over the course of history. Much of Greek and Western thinking was shaped in Egypt.

Eratosthenes figured out the circumference of the earth in Alexandria, (yes, the Greeks knew the earth was round), Euclid came up with geometry in Alexandria, and while Ptolemy and his descendants tried long and hard to be Egyptian, they ended up spreading Greek culture throughout Egypt.

It was also in Egypt, where the church fathers reconciled their ancient past by asking such questions as: Where does ancient Greek philosophy fit into our Christian worldview? Can non-Christians be saved? And how does one become one with God, or as we know it today as Theosis, which is at the core of Greek Orthodox Christianity today.

During the Greek Revolution, Constantine Kanaris was sent on an ambitious covert naval campaign to destroy Egypt’s naval fleet that was docked in Alexandria’s port. Egypt and Ibrahim Pasha were planning to invade the Peloponnese on behalf of the Ottoman Sultan and reclaim Greece for him.

When Kanaris came near the port he lit his Greek ships on fire and sent them towards the Egyptian fleet. His ships veered off the last minute missing the fleet, but setting part of the port on fire. Kanaris’ naval ingenuity nonetheless set shockwaves around the world for the Greek people’s courage and will to be free.

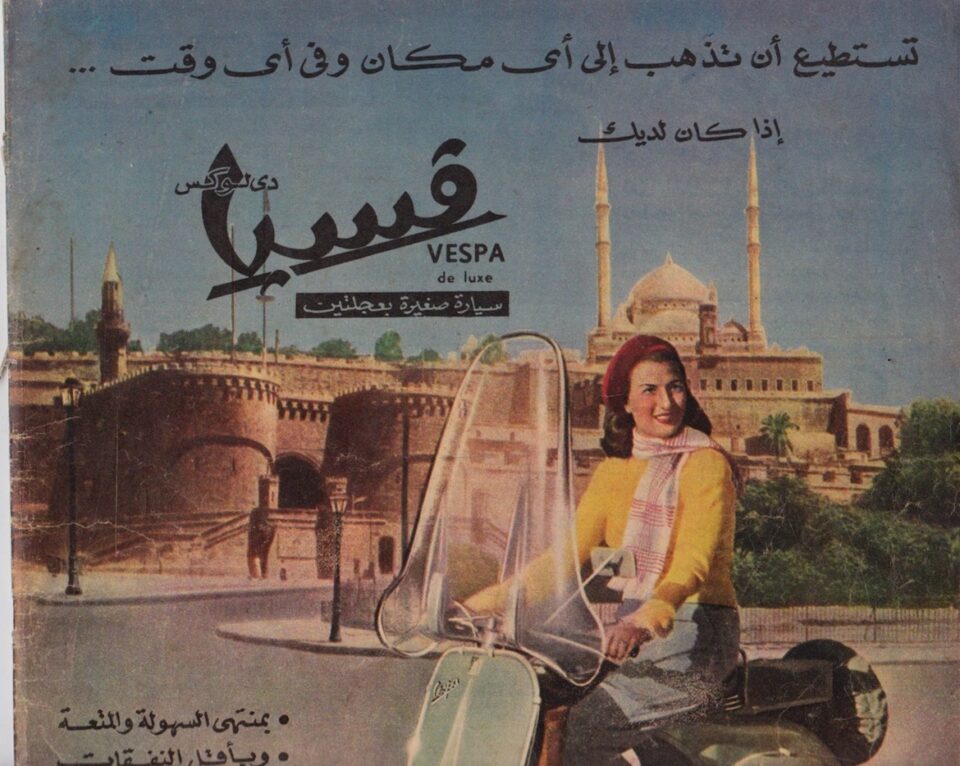

One day one of my students commented to me that she hated visiting her grandmother because her grandmother teased her for wearing a hijab, she said, “My grandmother says when she was young girl she could wear shorts and a tank top-and ride a bike in the streets of Cairo without being harassed. She says I look like the cleaning lady.”

Pull up any old photos of Cairo and Alexandria from the 1920s to about the early 1960s and you see a very different Cairo. Within two generations things in Egypt changed very fast. Cities like Alexandria and Cairo were cosmopolitan centers — more so than most European cities of the time.

Egyptians, Greeks, Armenians, Italians, French, Syrians and Jews all lived and worked in harmony with one another. By the 1950s, Pan-Arabism was on the rise in Egypt and anti-colonial sentiment was popular among many Egyptians. Many Europeans decided to leave Egypt.

But can a people choose what is good colonialism and what is bad colonialism? Egyptians apparently have. They have for the most accepted their Arab and Islamic past, but rejected their European past. It is not just Egypt though. After the Greek Revolution, Greeks welcomed theirr ancient Greek and Roman (Byzantine) past, but rejected their Ottoman past.

When in Egypt however, there is no doubt a sense of loss and nostalgia for many Egyptians when talking about the Greeks and the past in general. Many Egyptians see early 20th century Egypt as their Bell Epoque. This is when the streets of Cairo were clean and orderly, when women wore the finest European clothing, men nicely tailored suits and fez hats and people felt free to speak their minds.

The Greeks did well in Egypt, in business, trade and art. They made a lot of money, like the Benaki, the Averoff and the Gianclis families. They were great writers like Penelope Delta and Constantine Cavafy, and there were artists like Nelly Mazloum, Jean Desses, Nikos Tsiforos, Maria Giatra Lemou and Jani Christou who came from Egypt.

After Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Pan-Arabism initiative many Greeks felt they had to leave. They fell in the category of colonialist even though many of them had been in Egypt since Ptolemaic times. Most moved to Greece and Australia.

I was shopping one day with a friend at the Khan el-Khalili Bazaar in Old Cairo. I was told beforehand by my friend that if the shopkeepers ask where I was from to just say Yunani (Greek), that way I could avoid overpaying.

I came across a shop with souvenirs and the shopkeeper asked me where I was from. I said, “Yunani” and he said, “Ah, Yunani” and a story about the Greeks in Egypt followed. That day, I heard several personal stories about the Greeks in Egypt from Egyptians. They were about playing with Greek kids when they were kids, to stories about their neighbors who invited them for dinner during Easter, to when their parents or grandparents still missed their Greek friends when they left.

There is no question a sense of loss for many Egyptians when it comes to the Greeks. The Greeks were in Egypt before many others. They helped make modern Egypt as Professor Kitroeff argues in his book. But it’s hard not to feel sad when walking through the streets of Cairo and Alexandria and thinking how different this place once was.

Featured image at the top of the article: Family of Emmanouil Benakis. Alexandria, Egypt, early 20th century. (Photo / Alexandros K. Samaras collection)

About the Author

Dr. Theodore Zervas is a distinguished visiting professor of comparative and international education at the American University in Cairo, Egypt.