When the lights came on at the Astor Cinema at the end of the Athens premiere screening of Valerie Kontakos’ new documentary film Queen of the Deuce almost a year ago, I realized I had just watched a film about Greek America like none other.

The film is about Chelly Wilson, a Greek American who lived a life that was unique and extraordinary but also quintessentially Greek American in that it was driven to success by a sharp business acumen, a strong work ethic and a willingness to take risks all the while being also a devoted mother and grandmother with a wide circle of beloved friends.

Chelly began her rise to fame by promoting Greek films in New York. But what came next was the extraordinary part of Chelly’s life which was, well, so extraordinary, that Greek America has preferred to ignore it and keep it under wraps. She left her mark on New York nightlife as a taboo-shattering feminist, a lesbian owner of porn and gay sex cinemas and a major player in the erstwhile “seedy” world around 42nd street in Manhattan from the late 1960s to the early 1990s.

That is not the image Greek America likes to portray when it tells stories about itself, that talk about being entirely a law-abiding, family-loving and church-going community. That narrative made sense before World War II when racists and xenophobes opposed to immigrants exaggerated the instances when Greek Americans fell afoul of the law. It was sustained after the war when the Greek Americans had gained acceptance and responsibility.

For example, when AHEPA’s president, Louisiana oilman William Helis appeared before the U.S. Senate in 1949 to support a bill that would allow 50,000 Greeks displaced from their homes during the war to emigrate to America, the incoming Greek refugees would not be a burden on America, Helis stated, because they would manage just as well as the Greeks who were already in the country, who “almost without exception the Greek Americans are respected as law abiding and useful citizens.” And this assertion was echoed consistently by community leaders ever since. In doing so, they in fact censor our knowledge of lives like Chelly’s and by extension the diversity and richness of the Greek experience in America.

Of all those Greek Americans whose lives undermine the official narrative there is none more edgy and outrageous– and impressive in terms of achievements– than that of Chelly Wilson, the subject of the “Queen of the Deuce” documentary film.

How this film was made in the first place is a small miracle. Kontakos had worked as a cashier at one of Chelly’s film theaters on Sundays, when it screened Greek films. Athens-based writer Christos Asteriou, while in the United States doing research on a novel, learned of Chelly and her porn cinemas from an uncle who worked at a photography store next to one of those theaters. Kontakos and Asteriou joined forces and thanks to a team of collaborators Kontakos assembled we have an extraordinary story on film.

Chelly was born in Thessaloniki as Rachel Serrero of Sephardic Jewish parents. She barely managed to get out of Greece sailing on the last ship that left Piraeus before the outbreak of the Second World War during which the Nazis sent most of Greece’s Jews to the gas chambers.

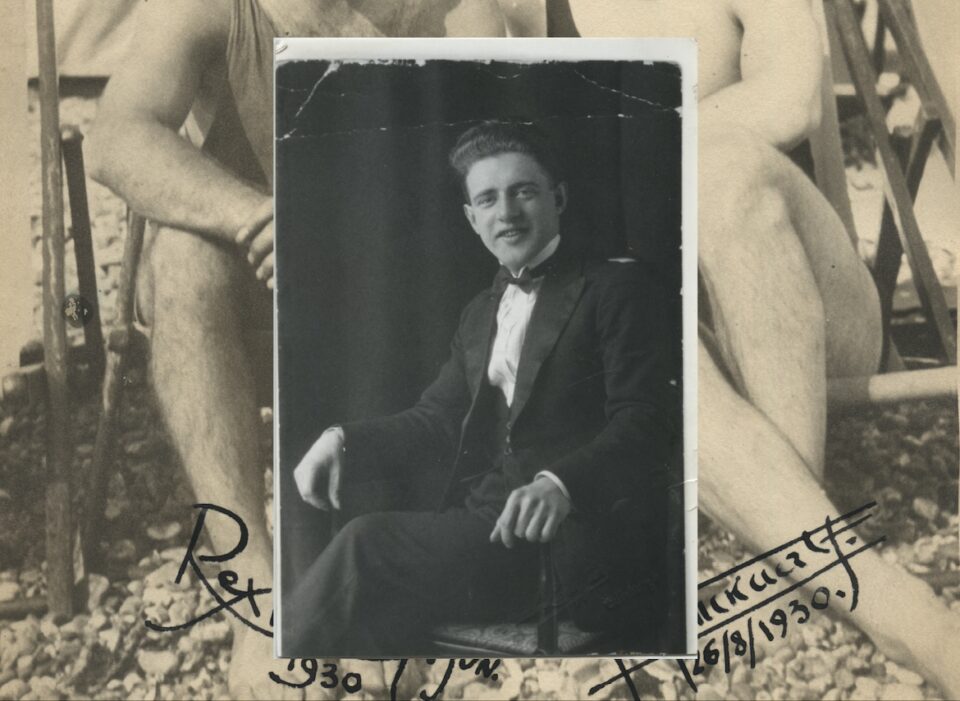

She began by working at a hot dog stand at Coney Island but by the 1960s she was renting a cinema on Manhattan’s Eighth Avenue where she screened art films and on Sundays popular Greek films. In between, she managed to go to Palestine, find her two children who had remained hidden in Greece during the war and bring them back to America, where they joined Bondi, the child she had with her second husband, film projectionist Rex Wilson.

Her connections with the film world in Greece ran deep. She was one of the co-producers of films made by the up and coming filmmaker Nikos Koundouros including a couple of classics, To Potami (The River) and Mikres Aphrodites (Small Aphrodites). Another Greek film she produced was O-Key Phile (OK Friend). It is about a Greek singer who goes to America to further his career, gets involved with drugs and the mafia and decides to return to Greece.

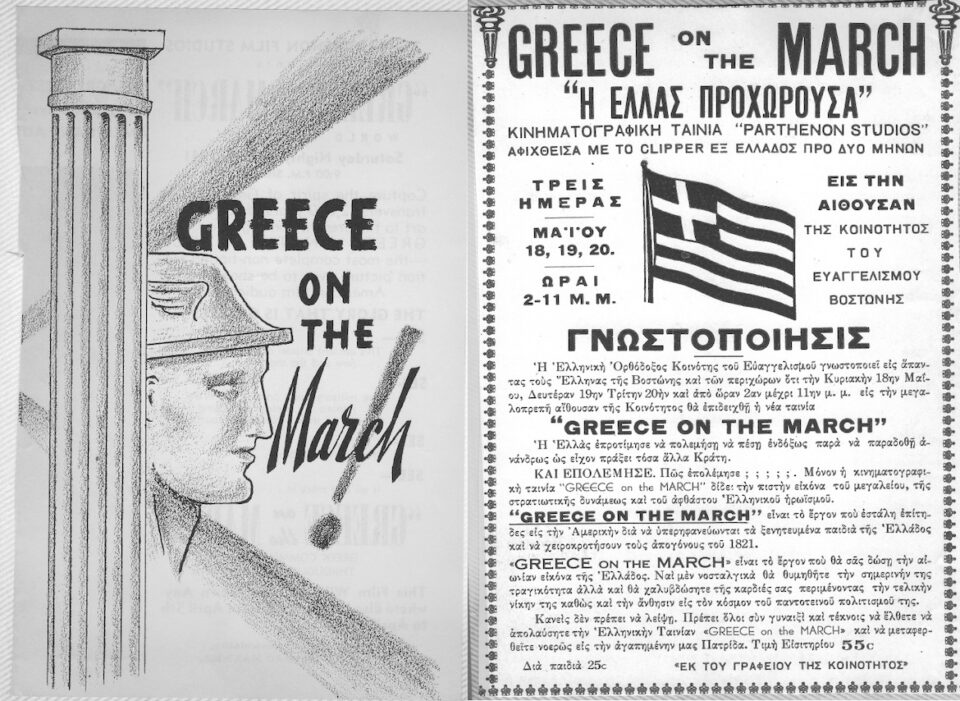

Passionate about her homeland, she also made a film early in her career called “Greece on the March” and screened it in Greek Orthodox communities throughout the United States to raise money for the Greek relief efforts during the Nazi German occupation.

Chelly, in contrast, encountered New York’s underworld, but stayed, survived and thrived. She began acquiring several cinemas on Eighth Avenue and around 42nd street in Manhattan, and when the obscenity laws in America began being loosened she transitioned into screening soft core pornographic films and then hard core ones. This was when 42nd street, known as “the Deuce,” the lowest ranking card in the deck, was lined with go-go bars, sex shops, peep show establishments, adult cinema theaters, drug dealers and sex workers.

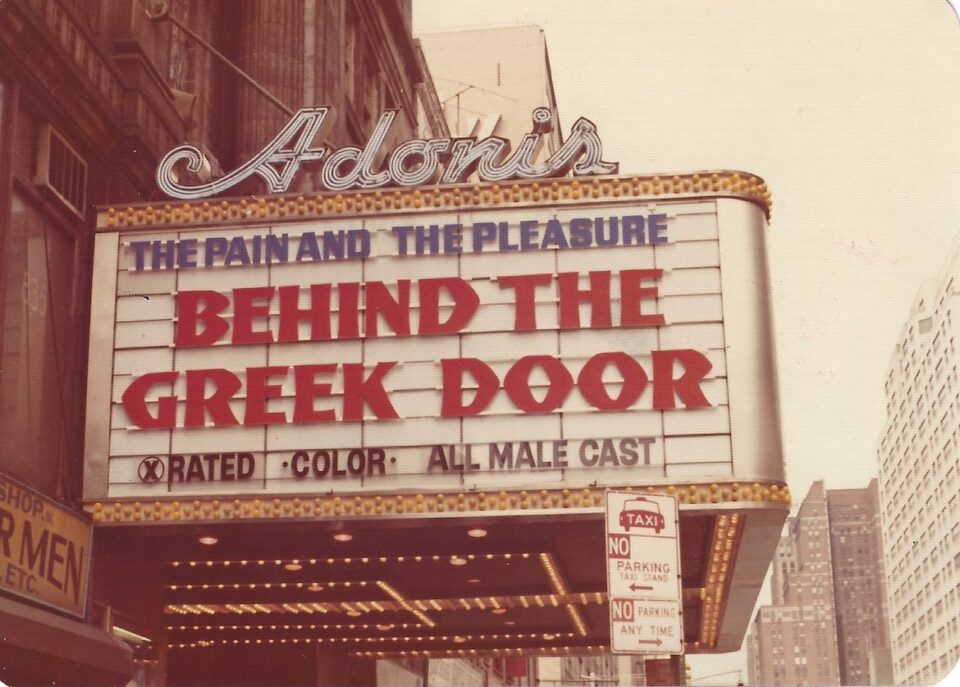

Officially, Chelly owned six cinemas, among them the Eros, the Venus and the Adonis but she was also a part owner of over a dozen, a remarkable business achievement. She also owned several cinemas in Puerto Rico. Greek America’s histories celebrate the life of a Greek-born immigrant from the Peloponnese, Spyros Skouras who owned cinemas in St. Louis, and eventually became the head of Twentieth Century Fox Studios.

Well, there is certainly a place for Chelly in the pantheon of Greeks involved in the cinema business in America. And while not discounting the cut-throat competition in Hollywood, we can say that Chelly had to face a much more difficult environment and navigate in between over officious policemen and the organized crime networks that operated in and around 42nd street.

Many of the films that screened at her theaters were actually produced by a company she herself co-owned, cutting out the profitable middle man. Some of the titles of the films her company produced were “I Want You,” “Whip’s Women” and “Come Ride the Wild Pink Horse.” Chelly lived above the all-male Adonis Theater that she owned, entertaining her fellow poker players and female lovers with her thick Greek-accented English.

The Adonis on Eighth Avenue between 50th and 51st Streets was New York City’s largest and most popular gay adult movie theater. In the 1970s, known as the Tivoli, it was operating as a ‘straight’ adult movie theater up to February 1975. The following month it became one of New York’s most popular adult all male film theaters, renamed Adonis Theatre, and operated successfully until it was closed in 1989.

Chelly’s decision to screen gay films in the Adonis was both a savvy business move and also culturally and socially progressive. For many gay men who came out in the period after the Stonewall riots in New York in 1969, the seventies were a golden age of sexual freedom. For the first time they were able to openly acknowledge their homosexuality and foster a sense of identity and community. The Adonis became part of that trend which would be stymied with the advent of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s.

By the mid-1970s Chelly had become one of the most savvy and charismatic figures of the sex-related industry in midtown Manhattan. She needed her wits about her, because her businesses may have been legal but were under threat because of challenges to the laws or because a police raid in one of the cinemas could discover “lewd behavior” going on among its patrons. The legality of Chelly’s business may have been legal because the 1970s had witnessed more liberal treatment of pornography compared to the past but that legality was fragile because of constant challenges.

A federal Commission on Obscenity and Pornography established in 1970 treated pornography more liberally stating that both obscenity and pornography were in the eye of the beholder and to an extent ought to be permitted under the laws protecting freedom of speech. In some cases whether a film depicting sexual acts was deemed “lewd” and therefore an affront to community standards would depend on whether it had a story line, in which case in court it could be considered as social redeeming.

In terms of the state laws governing its regulation, New York state laws were based on vague notions such as community consensus in determining obscenity and this resulted in an inconsistent treatment of the porn cinemas around Times Square. On top of the inconsistency came a conservative backlash that would grow steadily.

This twilight zone in which the sex industry found itself fostered illegal practices. We can assume the organized crime organizations offering protection, persons in authority may have been offered bribes and what went on in the theaters during the screenings of the sex films is anyone’s guess. Chelly was able to navigate through this challenging environment and make the right moves.

The shopping bags stuffed with cash that visitors to Chelly’s apartment stumbled over indicate that she knew how best to protect the profits most of which she generously distributed to lovers, relatives and friends and persons who enabled her businesses to continue to operate.

In contrast to Greek America’s unwillingness to acknowledge, let alone recognize Chelly, she was extremely popular with both American and Greek celebrities. In the late 1960s she opened a dinner dance restaurant, the Mykonos on West 46th Street. The original purpose was to enable her lover Noni Kantaraki to sing there. The interior was designed by Vasilis Fotopoulos who won an Oscar for his art direction in the film “Zorba the Greek.”

Chef Evangelos Molfetas was invited by Macy’s department store to cook Greek Easter specialties in 1976. The restaurants patrons included President John F. Kennedy and his wife Jackie, Shirley MacLean, Aristotle Onassis, members of the Embiricos and Goulandris shipowner families and Melina Mercouri, who said of the restaurant when she visited in 1968 “Before I tasted the food or heard the music, just at the entrance I knew I was home.”

Chelly stopped making films in the 1980s, and slowly moved away from the adult business. She died on Thanksgiving Day in 1994 after multiple heart attacks. Naturally, she left detailed instructions for her funeral and the party she wanted her family to hold in order to celebrate her life.

Pornography and the Mafia

The world that Chelly had to steer through became all the more complicated because organized crime was moving into the pornography business. A front page article in the New York Times in December 1972 discussed the ways this was happening. The investigation the article was based on was undertaken by two young reporters, the Greek American Nicholas Gage and Ralph Blumenthal.

They wrote that in New York City organized crime dominated the illegal production or reproduction and distribution of pornographic movies, books and magazines. The profits they could make through their activities that undermined the normal practices of operators such as Chelly were huge. For example an associate in the Colombo family, opened up a laboratory in Staten Island to mass produce hard‐core pornographic films. When Federal agents raided one of the laboratory’s distribution centers they found 50,000 reels of hard‐core porno graphic films.

Each of those reels which were copies, reproduced without copyright permission that cost about $3 each to print in color and were being sold at retail prices ranging from $25 to $65. The two reporters also found that another reason the mob was moving into this line of business was the legal uncertainties of the legal framework surrounding pornography and its definitions: “Confusing and sometimes contradictory court decisions make distributing pornographic material a lot safer than making book [illegal gambling], selling heroin or loan‐sharking,” they wrote.

Another profitable side to this business was controlling the peep show machines, booths in which one inserted coins in order to watch images of naked women and later on of men. The brutal practices surrounding the control of this form of accessing this form of pornography would involve another Greek American who is also absent from conventional stories about the community’s history.

The Greek American Porno-King of Atlanta

Chelly may have operated in a twilight zone between legality and illegality, but another Greek American operating in the porn business, where he would gain notoriety, did not avoid becoming involved in out and out criminal activities. Michael Thevis has been described as the “Porno-King of Atlanta” and the “Scarface of Sex.”

Thevis grew up in Raleigh, North Carolina and was raised by his grandparents who had emigrated from Sparta – his parents had divorced. Young Mike started off life in the same way as did thousands of other Greek Americans who grew up in the Depression-era 1930s, having to work from a young age. This, he recounted later, gave him a hunger for the good things in life, and earned him an early conviction for attempted robbery. Prior to that he had served as an altar boy at Raleigh’s Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church.

In search of the good things in life, Thevis moved to Atlanta, where he struggled to make a living as a businessman until he went on a business trip to New York and came across a peep show machine that displayed slides of naked women. He returned to Atlanta and with the help of a local locksmith he manufactured a more sophisticated version of those machines, and began selling them across the country.

This was the time when the Supreme Court began liberalizing obscenity laws and Thevis’ business turned to be a gold mine as he himself described it. As one of the articles on Thevis’ life explains, this money making machine “was like a jukebox for porn, with an 8mm projector that played a 15-second loop of erotic film. Thevis leased them to adult bookstores, where the lustful and the curious locked themselves in a private booth and kept the action rolling by feeding it quarters. During the sexual revolution of the 1970s, the peep machine racket would earn an estimated $2 billion.” Thevis would become a millionaire well before his 40th birthday.

Thevis’ fall was almost as precipitous as his rise to money and fame – or infamy. Competitors appeared using underhand means to copy his success. But Thevis was not one to step down. In 1970 he shot and killed a business rival, he burned down a rival’s warehouse, and was involved in several other illegal activities including the murder of another rival.

He was arrested multiple times and escaped from prison, was placed on FBI’s Most Wanted List and was arrested by the FBI several months later, in November 1978. The next year he was sentenced to life in prison. Thirty-four years later, in 2013 he died of heart and respiratory failure in a prison in Minnesota at the age of 81.

Pittsburgh’s Garden Theater

The name of the American writer Horatio Alger is often used as an adjective to denote success achieved through self-reliance and hard work, themes in that writer’s fiction. Strangely enough a Duquesne University Law Review article describes George Androtsakis, a Greek American porn-cinema owner as a modern-day Horatio Alger.

Androtsakis’ story is yet another Greek American chronicle of struggle and success. He arrived from Greece in 1968, found work as an usher in a movie theater. From there, we learn from the authority of a Law Review article “he worked his way up in the movie industry, eventually becoming the owner of a number of theaters featuring foreign-language, mainstream, and adult films.”

One of the cinemas he owned was the Garden Theatre located on North Avenue, the primary thoroughfare of the Northside neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and ironically just steps away from one of the city’s thriving Greek immigrant neighborhoods with Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church at its epicenter.

In 1995, the Pittsburgh City Council’s $40 million plan for the redevelopment of the neighborhood involved acquiring Androtsakis’ Garden Theater cinema. While the city of Pittsburgh started buying up the buildings in the area, Androtsakis refused the city’s buyout offer. He argued, in what became a nine-year long legal struggle, that city leaders would quash moviegoers’ First Amendment right to see adult films — and his right to show them — by closing Pittsburgh’s last remaining adult theater.

Restrictive zoning laws make it unlikely that he could reopen elsewhere in the city, Androtsakis claimed. Thus the Garden Theatre became a battleground between a business owner who asserted his right to display adult films and the City of Pittsburgh that demanded the right to fight the deleterious effects of urban decay.

The case reached the Pennsylvania Supreme Court where Androtsakis finally lost. The state’s highest court said the city’s Urban Redevelopment Authority did not violate the free-speech rights of the owner when it tried to acquire the cinema through eminent domain.

Passaic N.J.’s Montauk

Luckily for Androtsakis, he owned adult theaters in New York and co-owned Passaic, N.J. The cinema in Passaic, whose principal owner was another Greek American James Bochis also had several run-ins with the authorities in the 1970s There was a raid by the police in July 1974 because it was screening the film “The Devil in Miss Jones” which is considered a classic pornographic film and had caused a sensation when it was originally released in 1973.

Newspaper reports indicated that it was Bochis’ company which made Miss Jones and that experts agreed with his contention that the film had a clear story line and a socially redeeming message. The day the police descended on the Montauk cinema, the star of the movie Georgina Spelvin was in the lobby making a personal appearance and signing autographs. She was taken into custody along with Bochis, who also ran into trouble with the law after a screening of “The Devil and Miss Jones” in a cinema he was associated with in Rochester, N.Y.

In response to the raid the Montauk switched from showing hard core to showing soft porn films which were permissible. With obscenity standards being relaxed, within a few months “The Devil in Miss Jones” was being screened throughout New Jersey and all-summer long in Atlantic City. Bochis went on to produce adventure films as well as “The Devil in Miss Jones 2” a sequel which built on the original story line with a comedic bent, according to film reviews.

The police action in Passaic and Rochester was the result of a U.S. Supreme Court decision that caused a fundamental shift in authority over who could define and prosecute obscene material. No longer would a national standard prevail and thereby protect sex films; from then on, communities would be able to determine local thresholds for the public. In some ways, Chelly was better off in liberal-minded New York than other Greek Americans who owned cinemas that screened pornographic films.

Boston’s Symphony Theaters

James Vlamos and Serafim Karalexis who operated the Symphony Theaters, a twin-cinema in Boston, owned by fellow Greek American Steve Prentoulis were found guilty in 1969 for showing an obscene film, I am Curious Yellow.

Prentoulis was no stranger to situations in which his Symphony Theaters were targeted by the authorities for showing Swedish films that included “nudity.” His small distribution company dealt also with other foreign films, including a 1966 film entitled “Woman and Temptation” starring a former Miss Argentina Isabel Sarli. In the film she falls in the river and ends up in a jungle where she arouses the passions of the native inhabitants.

Prentoulis and Vlamos had also collaborated with Greek American film director Greg Tallas in the making of “Assignment Skybolt” a spy movie set in Greece with music by Manos Hadjidakis. I am Curious Yellow, made in Sweden in 1968, was an erotic drama film that included nudity and sex that became somewhat of a cult movie.

The obscenity statute on which two Greek Americans were convicted was already under constitutional attack in Massachusetts and there ensued a legal struggle that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, with the Byrne v. Karalexis case. The state’s Attorney General Robert Quinn – the same Quinn whom Mike Dukakis would defeat in the race for the Democratic Party nomination for Governor in 1974 – traveled down to Washington D.C. to argue the case. The film was ultimately judged not to be obscene.

Defending the right of the Symphony Theater to screen the film was a young Harvard Law School Professor, Alan Dershowitz who would soon gain national fame by taking on more high profile and controversial cases. The film would go on and gross $20.2 million, a record for a foreign film in the United States at the time. The Symphony Theaters would close in 1977, and in bidding them farewell the Boston Globe described the opening of I am Curious Yellow in 1969 as their moment of glory.

Chelly’s Legacy

Valerie Kontakos’ wonderfully conceived and beautifully made film goes well beyond a deserved homage to the life and times of Chelly Wilson. Yes, Chelly was unique in many ways and there may never be a similar story anywhere in the rich and diverse history of the Greek American community.

Chelly was a Greek woman who escaped the Holocaust in WWII, emigrated to the U.S., and married a slew of men while being openly gay and survived and thrived in one of the most difficult business environments in the world, that of New York’s 42nd street and its environs in the 1960s and the 1970s.

But Chelly story is also a reminder that there were also Greek Americans operating in the twilight zone of America’s porn industry in the 1960s and 1970s and by doing so were challenging the conservative morality of the times, advancing the cause of free speech and free choice and enabling thousands of persons to come to terms with their sexual preferences and their sexual orientation.

Queen of the Deuce Film Trailer

Bibliography

My thanks to Valerie Kontakos and Christos Asteriou for generously sharing time to discuss the making of “The Queen of the Deuce”.

Sarah Andrews “The First Amendment as a Shield to Eminent Domain – An Opportunity for Responsibility in Pennsylvania” Duquesne Law Review Volume 44 Number 3 Article 6, 2006.

Ralph Blumenthal and Nicholas Gage, “Crime ‘Families’ Taking Control of Pornography” New York Times December 10, 1972.

Jeffrey Escoffier, “Sex in the Seventies: Gay Porn Cinema as an Archive for the History of American Sexuality” Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 26, No. 1 (January 2017).

Jeff Maysh, “The Scarface of Sex: The Millionaire Playboy Who Murdered His Way to the Top of Porn” Daily Beast, June 16, 2017

George McKinnon, “Boston Man Harried by Censors for Foreign Fare” Boston Globe July 1, 1968.

Bonnie Pfister and Bobby Kerlik, “High court upholds seizure of X-rated theater” TribLive Dec. 28, 2006.

Eugenia Sheppard, “Get a Bouzouki, Dance the Syrtaki” Democrat & Chronicle, December 23, 1968.

Bette Spero, “Visiting Porno Queen Enjoys Stardom” The Daily Register September 14, 1973.