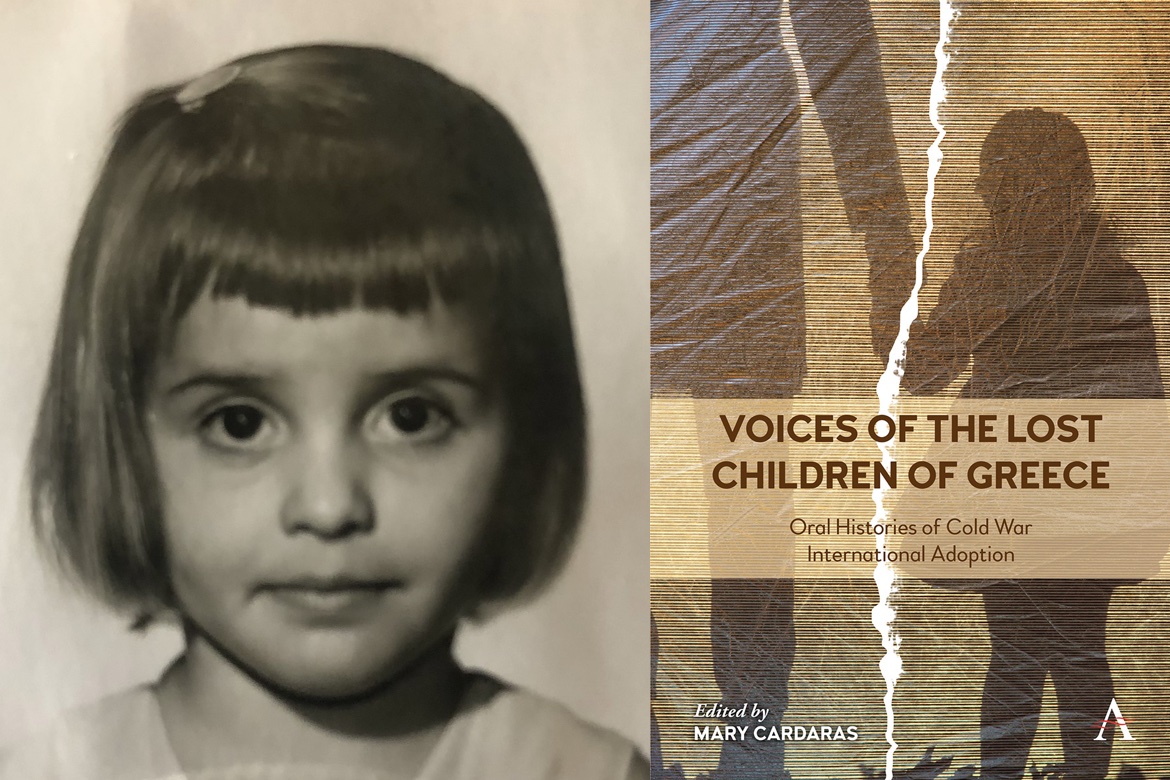

Four years ago, I experienced the death of my mother, Amalia. It was one of the saddest days of my life. I felt untethered, alone and abandoned. I was going to miss her laughter, her sense of humor, her curiosity about the world around her, her love of people and her smarts. I was going to miss her being there and the sound of her voice. I could not wrap my head around the fact that I wasn’t ever going to see her again. At the funeral, at the final goodbye, before they closed the casket to take her from our Greek church to the cemetery, I could not take my eyes off of her because I knew it was going to be the last time. In the days to follow, I wanted to look at pictures of her as grief began to take hold.

And there was the startling realization: I was back to where I started.

Motherless, an orphan all over again.

You see, Amalia was my adoptive mother. She was a loving mother, a good mother, and with my father, Aristotle, provided a good home and a life with a large, extended Greek family. I am grateful that my adoption was to another Greek home. I didn’t lose my language, my culture, my religion. I had a strong sense of what it means to be a Greek and what we value. But I did lose something, and that was to know who I was before I became the daughter of new, Greek-American parents.

My mother’s death and the death of my father 20 years before opened a door I had not anticipated ever walking through. With their absence I was now free to get in touch with my feelings about my own adoption. In adoption, in order to create a new family, another had to be destroyed. I was never a real orphan. I had a first mother, the one who gave me life. I had a father. Who were they? Where were they?

There were many stories told to me over the years about my origins and how I came to the United States. But as time passed, memories faded, stories shifted, and the truth became more and more obscured. And to be honest, no one else thought it was of any great importance. But it was to me. I felt an obligation to myself to figure out who I was and from where I came.

I started my journey taking Greek language lessons at the Greek Orthodox Church in Oakland, California. We were a small, cohesive group, which included a Greek-American woman to whom I have since become very close. She told me a story, an incredible story, a painful story about her cousin, an adopted person who was stolen from Greece and from her parents who were very much in love. As a journalist, but more as a fellow adoptee, I needed to meet Dena Poulias and convince her to let me tell her story.

In the course of my research about Dena and after a year of interviewing her, I was led to a book called Adoption, Memory and Cold War Greece: Kid pro Quo? (University of Michigan Press, 2019) written by the noted modern Greek scholar and Koraes Chair at King’s College London, Gonda Van Steen. Her book revealed an ugly time in Greece’s history after two wars, World War II and a civil war, which pitted Greek against Greek. She reminded the people of Greece about this painful chapter in their history and she educated other Greeks who had no idea about what happened.

And what happened was a mass export of children from the country. Before the world experienced the mass adoptions of the Koreans, the Chinese, the Romanians, the Irish, and the Guatemalans, there were the Greeks. We were the first.

Four thousand Greek babies and children were sent away for adoption to points all over the world, mostly to the United States. There were many legal adoptions. But there were others, overshadowed by nefarious circumstances and practices. Many children were brokered. Some were sold to the highest bidder. Mothers were encouraged, pressured to relinquish children to fulfill a market need for white children from abroad. Fathers were not even factored in, some not even knowing they had fathered children who were given away. And babies were stolen. There is story after story about parents during that period in history being told their new born babies had died. Nothing was recorded. No evidence. Bodies vanished from hospitals and parents were left with broken hearts, which has affected them, haunted them and their families their entire lives. And to this day.

I was incredulous. Had I been living in a cave? Why hadn’t I been educated about this history? Was I part of this wave? I learned that I was, as I was writing Ripped at the Root (Spuyten Duyvil, 2021), the adoption story of Dena Poulias. After the publication of Van Steen’s book and my own about Dena, I spent a good deal of time with Gonda in Greece as I tracked down my own adoption story like I never had before.

I was interviewed for a number of newspaper articles, was on television, on radio, on webinars, and at the stoic and iconic Gennadius Library to talk about what it means and what it feels like to be an adopted person. I met other activists around the world and authors equally critical of abuses in adoption placements.

Gabrielle Glaser, journalist and author of American Baby: A Mother, A Child and the Shadow History of Adoption (Viking, 2021), now a close friend and confidante, taught me that my feelings were real and valid and, most importantly, that I was entitled to them. I was not disloyal to anyone. I was not ungrateful. This was my life and I needed to know about all of it. The adoption has affected me and many aspects of my life, for all of my life. And I realized, meeting and talking to other adoptees over the years, that what happened has affected the other 3,999 of us as well.

We have stories to tell and our fellow Greeks of the vast diaspora and in Greece need to hear them. Voices of the Lost Children of Greece (Anthem, 2023) is a compilation of 14 stories, a small sample of stories from hundreds of Greek-born adoptees out there, mine included, which tell unvarnished, raw, lived experiences of loss and trauma and insecurity and pain. The people in this collection are all different and bring different perspectives, but there are striking similarities in all of our testimonials. I am grateful that the collection will also be translated into Greek later this year by Potamos Publishers in Athens.

You’ll meet Maria and Robyn who suffered both emotional and physical abuse and were adopted by parents who were not properly vetted. You’ll meet Robert who was raised as an only child and separated from a sibling. David’s mother wrote letters to him all her life, hoping that one day her baby would return to her. Alexa was traumatized at the orphanage and has memories about it because she was there up until age four. Nick and Ellen and Merrill were left as foundlings at the Patras orphanage. Sonia, who was adopted by Dutch parents, learned long after the fact about her birth mother’s serious illness which could have impacted her own health. And Chris was given away by her own mother at age seven, forcing her far away from the Greek village and family she loved.

My own essay, the last in the collection, is really a tribute to a birthmother who has been in my thoughts for as long as I can remember. Birthmothers suffered so much and have been forgotten, discarded in many of these stories about adoption. I wanted to give mine a voice, too, a presence in my life, which she deserves.

My own search for details about my life recently led me to PIKPA (Patriotic Institution for Social Welfare and Awareness), a government funded agency, which holds many of our adoption records. I was there with journalist and friend, Katerina Bakogianni, who is doing a multi-part podcast about Greek adoptees, called Born Greek, which will be released this spring.

We sat across from a social worker who had my adoption file right in front of us, under her folded hands. She would not, could not let me see it, let alone have it. “There is nothing really of importance in it,” she told us, dispassionately. We need to protect the data, she said. But was “protecting” me from my data. That is my life in that folder, I told her. I have requested that file, through proper channels, with little to no response. It has been months now.

Greek-born adoptees want to be seen and heard and the time has come. We have been quiet and patient for decades. The Irish, the Spanish, the Koreans, the Romanians and other governments are coming to terms with their roles in the abuse stemming from the relinquishment and overseas adoption of their children. The Irish government, most prominently, has publicly come forward to apologize to the children, now adults, who suffered, and has opened all their adoption records to them. The same must happen in Greece. Please don’t make us wait as long as the Parthenon Marbles to return! Are the Marbles going to beat us home? Our fate is in the hands of the Greek, not the British government.

Thanks to Greek journalist Niki Lyberaki, Gonda Van Steen and I had what we thought was a pivotal meeting in 2021 with a former confidante of Prime Minister Mitsotakis. I was about to launch into my pitch for open adoption records and for Greek citizenship to be restored to those who want it. He stopped me mid-sentence, though, and said, “Mary, I get it. Nostos. Nostos for Greek adoptees. This is not complicated. With organization, this can be done quickly. And should be done quickly.” He was right. It should be done. And it is not complicated.

Last year, Van Steen had a heartfelt meeting with the President of Greece, Katerina Sakellaropoulou, who was open, sympathetic and kind. She is a mother herself and so understands, as any mother would, about what it would feel like to lose a child. Gonda gave her the book she wrote and asked for her support for a resolution to the issue.

But nothing much has happened since, except more meetings with others and empty sentiments about how badly people feel. Not much can be done, some have said. Data protection, others have said. We’ll think some more about it, they all have said. We’ve heard nothing specific in months.

To move the needle will take political will. Someone, specifically, must be assigned to the task of sorting through the papers, and held accountable for progress on the issue. We recommended a small task force comprised of Gonda and her advanced database that is based on her research, a Greek human rights lawyer, a representative of the government, and a representative adoptee. Those four could be sworn to protect the data and to vet those who come forward, proving who they are. At that point, records can be released to whom they belong, and the process for citizenship can be initiated. What could possibly be controversial or complicated? It wouldn’t even cost money. The expertise exists as does the will of volunteers to get the job done securely and expediently.

We are Greece’s children and we want recognition as such. We want the past to be acknowledged and we can help Greece itself come to terms with it. We are not wealthy benefactors, famous actors, directors or writers who are given Greek citizenship by virtue of their fame and dedication to Greece. We have an organic connection to the country. Born in Greece were we and born of Greek parents. We had no choice in the matter to our leaving. Most of us were stripped of every connection we would have had to the country. And we don’t ask for anything that was not once ours to begin with.

What greater tribute to Greece, what greater love is there for a country, any country, than for someone to want to be a part of it. Greece, don’t turn your back on us, your lost children. Turn toward us now with an embrace that shows the world that you will be part of the solution to a problem that has festered for years.

Listen to theVoices.

Step up, progressive in your attitude, and confident enough, as a small, but great nation that people have admired and turned to for centuries, to right a historic wrong.