The final chapter of the genocide that swept Turkey at the beginning of the 20th century was written in Smyrna, one of the richest and most cosmopolitan cities of the Ottoman Empire.

It was there, in Smyrna, where a small-town minister from upstate New York put together one of the most astonishing rescues in history. He saved the lives of tens of thousands of Christian women and children.

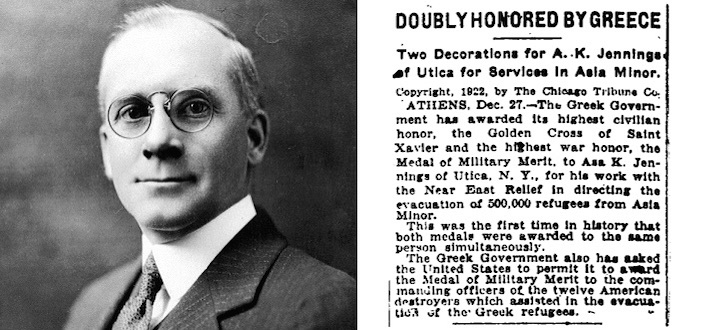

His name was Asa Kent Jennings, and his memory remains timely now that the problem of Christian persecution has arisen again in the Mideast and refugees are flooding out of Africa seeking safety in Europe.

Jennings was an unlikely hero. Barely over 5 feet tall with a crooked back that was an artifact of a bout with tuberculosis, Jennings had only recently arrived as an employee of the YMCA, which had a chapter in the city.

The time was September 1922, and the Turkish nationalist army had entered the city and soon set to slaughtering its Christian residents — both Armenians and Greeks. Smyrna was a polyglot city of Turks, Greeks, Armenians, Jews and Europeans, but it was predominantly a Greek-Christian city of about a half-million people.

Tens of thousands of refugees who had fled the country’s interior ahead of the Turkish army were packed in the city’s streets and churchyards and along its waterfront. Nearly all were homeless and destitute.

On September 13, the Armenian section of the city was afire — probably to dispose of the corpses that lay in the streets — and soon the fire spread to the rest of Smyrna. The city was a hell of heat and Turkish brutality for the helpless people gathered there. Nearly all of the refugees were pushed to a two-mile long narrow band of pavement of the city’s Quay between the fire and the sea.

Ironically, warships from Britain, the United States, France and Italy were in Smyrna’s harbor at the time of slaughter and fire and at first chose not to get involved. They had been ordered to stay out of the conflict. Eventually, the British saved a few thousands as the fire pushed the refugees into the sea, but when the fire died down, the rescue effort ended. About 80 percent of the city had been destroyed.

Hundreds of thousands of pitiful people were left to die on the city’s waterfront. Soon, hunger, thirst and disease began to take their tolls.

The situation seemed hopeless. There were no ships available or willing to transport the people from Smyrna, and the Turkish army began marching them into the interior, where they would be killed or often marched until exhaustion took their lives.

Then, incredibly, Jennings, who had set up a First-Aid station for pregnant women in a house on the waterfront that had been abandoned by its wealthy ethnic Greek owner, went into action. He later said that he had felt the hand of God on his shoulder.

The next several days would make history. Using a bribe, a lie and ultimately an empty threat, Jennings was able to assemble a fleet of Greek merchant ships and to enlist the help of the US Navy in a rescue plan. With the assistance of a brave young naval officer, who was skirting his orders, the Jennings evacuation removed a quarter-million refugees from Smyrna to the Greek islands and the cities of Piraeus and Salonika in only seven days. It was just in time to meet a Turkish deadline for their removal from the city or face deportations.

The small Greek port of Mytilene on the nearby island of Lesvos became the main staging area for the refugee boat lift. At one point, nearly 160,000 refugees camped around the city until they could be relocated to Greece. Under the strain of the enormous flow of refugees, Mytilene in turn became a nest of disease and starvation. Jennings continued his work there — arranging for Near East Relief to bring bread and medical supplies.from Constantinople.

After Smyrna had been evacuated, Jennings turned his attention to the rest of Aegean coast of Turkey and ultimately the long coast of the Black Sea, where many tens of thousands more Greek and Armenian refugees awaited rescue. By the time Jennings was done, the Greek Patriarch at Constantinople had credited Jennings with saving a million lives. Greece award him its highest medals for valor and service to the country.

Jennings’ story is mostly unknown to Americans, and he stands as one of the humanitarian heroes of the 20th century. Jennings, who died in 1933, remains a testament to the power of compassion in action. He had a courageous willingness to come to the aid of people in distress — people who are the victims of religious intolerance and war — qualities that would be welcome today.

Today, a monument dedicated to Asa Jennings and his heroic acts stands in the northern Greek city of Volos. The text (pictured below) reads “The savior of 300,000 Greeks in Smyrna in 1922” followed by “…within the heart of every man sleeps a lion…”

The story was adapted by professor Lou Ureneck from an original piece that appeared on Public Radio International and MSN. Asa Jennings’ story is told in Ureneck’s book, Smyrna, September 1922: The American Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century’s First Genocide, published by HarperCollins.

Is The Pappas Post worth $5 a month for all of the content you read? On any given month, we publish dozens of articles that educate, inform, entertain, inspire and enrich thousands who read The Pappas Post. I’m asking those who frequent the site to chip in and help keep the quality of our content high — and free. Click here and start your monthly or annual support today. If you choose to pay (a) $5/month or more or (b) $50/year or more then you will be able to browse our site completely ad-free!

Click here if you would like to subscribe to The Pappas Post Weekly News Update

1 comment

My paternal grandfather, Mihail N Zaharias, was a crewman on one of the Greek merchant ships that were used in the evacuation. He brought back with him to his home in Piraeus a 12-year old girl “Glykeria” who was one of the few survivors of a Greek village. His wife Evanthia welcomed Glykeria to her already unusually large family as a “ψυχοκορη” (a daughter of her soul). It wasn’t until 1956 that Glykeria was able to be reunited with a few members of her falily who had also survived the Turkish massacre of her village.