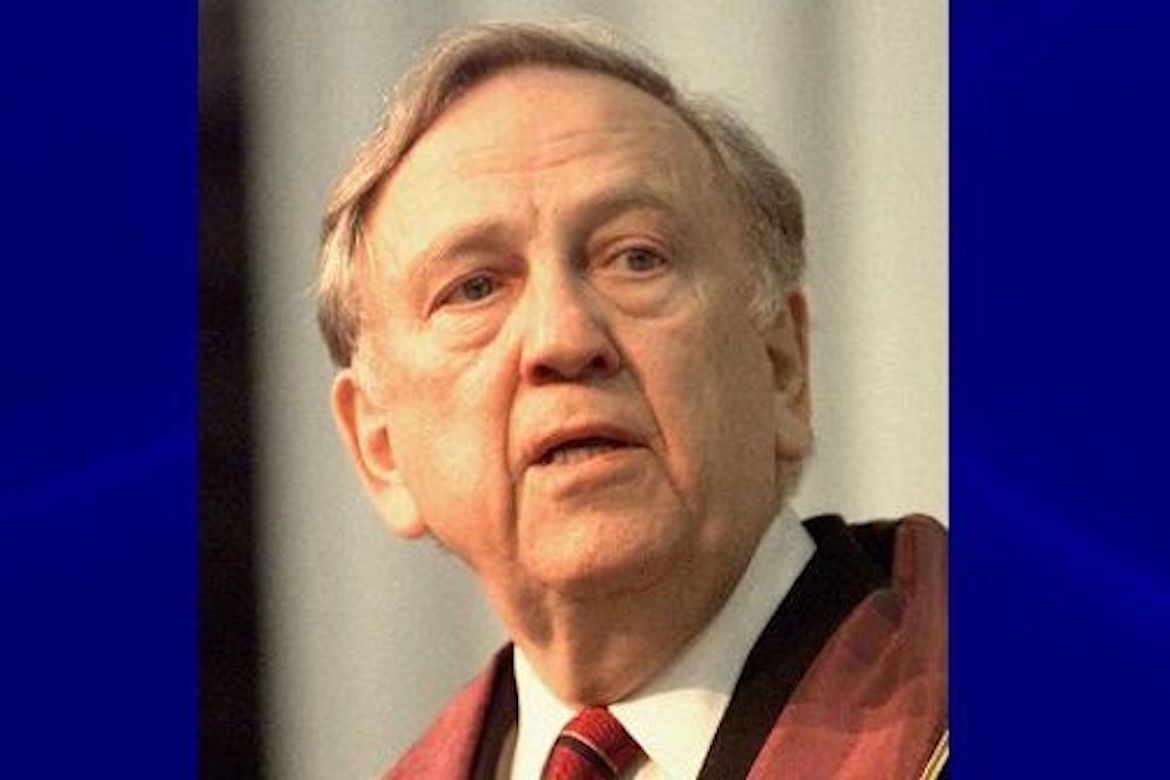

A leading figure in American politics during the turbulent decades of the 1960s and 70s — and a champion for Greek and Cypriot causes — Congressman John Brademas passed away on July 11, 2016 at the age of 89.

After politics, Brademas had become one of the most successful president in the history of New York University, elevating the school to its current level of prestige while raising more than $1 billion in endowment money and building numerous programs.

But Brademas’ true impact on Greek-U.S. relations took place in Washington DC during his years in Congress.

Brademas — first elected in 1959 as a member of the House of Representatives — was the second Greek American elected to Congress.

** NOTE: Brademas is erroneously referred to as the first Greek American elected to U.S. but that distinction goes to Lucas Militates Miller who emigrated from Greece to the U.S. as an orphan from the war of independence and was adopted by a Wisconsin family. Miller served the House between 1891-93. Brademas was the first U.S.-born Greek American elected to Congress, but that distinction is rarely made.

The Indiana congressman’s greatest service to the Greek cause came during the interrelated Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the military dictatorship in Greece.

He, along with Maryland Senator Paul Sarbanes, were outspoken and vocal critics of Turkey’s actions and the U.S. Administration’s appeasement of Turkey. Brademas fought against U.S. military support of Turkey and worked tirelessly in the early years of the Turkish occupation for a just solution to Turkey’s illegal occupation of the northern third of the island.

A July 30, 1969 letter penned by Brademas, who was known as the “Chief Greek” amongst his colleagues — and signed by 50 members of Congress — was sent to then Secretary of State William Rogers.

“We are writing to you because of our deep concern over the situation in Greece, the only European nation in the Western Alliance in the post World War II period to fall to a military coup.”

The letter criticized the Nixon administration for supporting the dictatorship and encouraged a cessation of its support, asking for “a clearer sign of U.S. moral and political disapproval of the dictatorship be given and sustained… and that U.S. military aid to Greece should not be increased, and indeed, should be curtailed.”

Throughout the military dictatorship in Greece, he vehemently opposed U.S. aid to Greece, seeking to penalize and not promote the military generals that had seized power.

He clashed openly with members of the administration, including (fellow Greek American) Vice President Spiro Agnew, who was openly supportive of the dictatorship, as well as fellow members of Congress who appeared favorable towards the military regime in Greece.

When Agnew visited Greece and praised the military rulers, Brademas criticized the move and said “that the U.S. should cease the policy wherein U.S. Government officials of the highest rank say warm and gracious things about the junta.”

Others he clashed with for supporting the regime in Greece were Congressmen Ed Derwinski and Roman Pucinski, and Greek Americans Peter Kyros and Gus Yatron, who believed that the junta saved Greece from communism.

Derwinski and Yatron were given decorations by the junta during their visit to Athens, after which Brademas went on record to say: “American officials in Greece don’t have to get their pictures taken with their arms around junta officials.”

Brademas used a famous quote in many of his speeches during his tenure in Congress which appeared to target numerous individuals and community organizations in the Greek American diaspora that either openly supported the dictatorship or remained indifferent.

“We Greeks invented democracy; some of us should practice it.”

Cyprus was another hot topic that Brademas actively pursued during his years in Congress, vehemently opposing Turkish advances on the island and a staunch supporter of Greece following the Turkish invasion in 1974.

Brademas was always quick to point out that his work on behalf of the Greek positions was in the best interests of the U.S.

He famously came face to face with then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger when the two met at the State Department on August 15, 1974 — in the days and weeks following the Turkish invasion.

Brademas told Kissinger, “We are placing the blame squarely on you, sir. We are not assigning responsibility for the failure of U.S. policy in Greece and Cyprus to President Ford. We feel it is yours.”

Opposing sides of the administration spoke openly and in private about Brademas’ passion for the Cyprus issue.

Brademas the fighter was discussed behind closed doors, as revealed in transcripts of de-classified meeting notes from a high level conversation that included the President of the United States, Secretary of State Kissinger and numerous powerful members of Congress about the Cyprus issue in September 1974.

“The fight isn’t over. Brademas will continue to fight,” Congressman Peter Frelinghuysen told the meeting participants about the Cyprus negotiations.

Brademas led a coalition calling for an arms embargo against Turkey. He and four other members of the House of Representatives who were of Greek descent (Peter N. Kyros (D-Me.), Gus Yatron (D-Penn.), Paul Sarbanes (D-Md.) and Skip Bafalis (R-Fla.)) rallied for the American government to enforce provisions of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 and Foreign Military Sales Act of 1968, which stipulated that weapons supplied by the U.S. could only be used for defensive purposes.

After facing vigorous opposition from Secretary of State Kissinger and President Ford, the coalition succeeded in passing a resolution to cut off military aid to Turkey. In 1978, however, the embargo was lifted by the U.S. Senate and supported by President Jimmy Carter.