The following was provided to us by Helen Zahos, an Australian nurse who spent several months of her own time volunteering in Greece, supporting and assisting relief efforts on the island of Lesvos and the border town of Idomeni. In her own words, and photos (below).

As I sit here in a quiet cafe in Greece sipping on a hot chocolate, I have some time to reflect on the last 10 weeks. I can only describe it as a roller coaster ride.

Late August I saw images on social media of the unprecedented humanitarian crisis that was unfolding; masses of refugees fleeing Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and neighboring countries descending on the small Greek islands neighboring Turkey.

A country already experiencing financial turmoil, Greece was being flooded with overwhelming numbers of refugees. Being of Greek descent, a registered Nurse and paramedic, I felt compelled to go and help when I saw the reports of the injured and lack of medical support available on the ground.

In the 6 weeks leading up to going. I decided to raise funds via an online crowd funding site, not expecting much of a response I was overwhelmed by the generosity of the people that donated. Within weeks $20,000 was raised for medical supplies and equipment.

The plan was to join the Medicine du Monde Greece team on the Island of Lesvos, and later move onto to the border of Greece and FYROM.

My very first day on Lesvos, I had just been picked up from the airport by a team member when a call was received. Over 3500 refugees had arrived on the other side of the island in the last 3 hours. There were reports of injuries and help was needed. We headed straight for that side of the island to assist.

The busses were not running as the police were overwhelmed with arrivals of refugees so they had forced the buses to stop. This left refugees in wet clothes and winter cold weather to hike the 10 kilometers up the mountain to the bus stop, to then be informed that no buses were running, only to then be faced with a 65 kilometer walk to Morya registration camp situated on the other side of the island.

Many of these people were carrying children. I asked why we couldn’t drop people off in our car. I was told that we would be charged with human trafficking of illegal immigrants if we were caught.

After helping a number of injured people, we realized that the greatest need for these refugees were blankets and clothes as the sun had set and they had to sleep on the side of the road. We organized for 500 blankets to be distributed that night. We joined forces with two other organizations and drove around handing women and children blankets that were asleep on the side of the road. We didn’t get back to the hotel until 3am only to be on the morning shift the following day. So began my time on Lesvos island.

Every day there were tales of tragedy, there were frequent drownings after boats capsized, people injured prior to arriving with wounds from bombings and shootings; chemical burns from the rubber boats they sat in leaked oil and fuel; pneumonia from spending nights sleeping out in the winter cold; swollen blistered feet from walking kilometers over mountains in wet shoes. Unaccompanied minors were turning up that had lost their parents on the journey; there were many disabled, blind and maimed.

They all had a story of survival from the war they had fled and the treacherous journey they endured. It became clear that no matter what the reason for leaving, this particular way of traveling was absolute hell and no one would chose this way of fleeing unless they absolutely had to do so and their life depended on it.

The children were the most difficult to watch suffer. The days when they were out in the cold and rain for up to 3 days with no change of clothes broke my heart. It was rewarding to be able to change them into dry clothes, organize blankets, food and supplies to get them through to the next part of their trip to the port of Mytilene and then to Athens. Their journey would take weeks to months from the time they fled their country, many days on foot carrying what little to no belongings they had.

One of the worst nights was the big boat accident on October 28th at approximately 5pm where 300 people were involved. The top deck of the wooden boat collapsed in the rough waves, 5 people in wheelchairs drowned instantly, 11 infants and 27 Adults died.

We still had 150 people lost at sea at 2am that following morning and with rough seas and freezing conditions we had lost hope of any more survivors. We had set up a church as a hospital and were treating patients all night long. Even the priest and his wife were running around distributing clothes and blankets and cups of tea.

In between treating patients I was comforting mothers and helping them search for their lost babies, knowing full well that they were probably amongst the 11 that drowned. I never let them lose hope as I helped them search through the crowds of survivors. In the following days I helped in the morgue helping the parents identify their children, including a mother who lost her 5 year old twins.

I will never forget the mother’s words– she said ‘we left to give you a chance in life from the war and we killed you ourselves instead’. I tried as best as I could to reassure her that the accident was not her fault. She told me she didn’t want to get on the overcrowded boat but the man in Turkey had put a gun to her head and said if they didn’t get on board the boat he would shoot her and her children.

Some of the hardest days were spent on Lesvos island where I welcomed refugees.

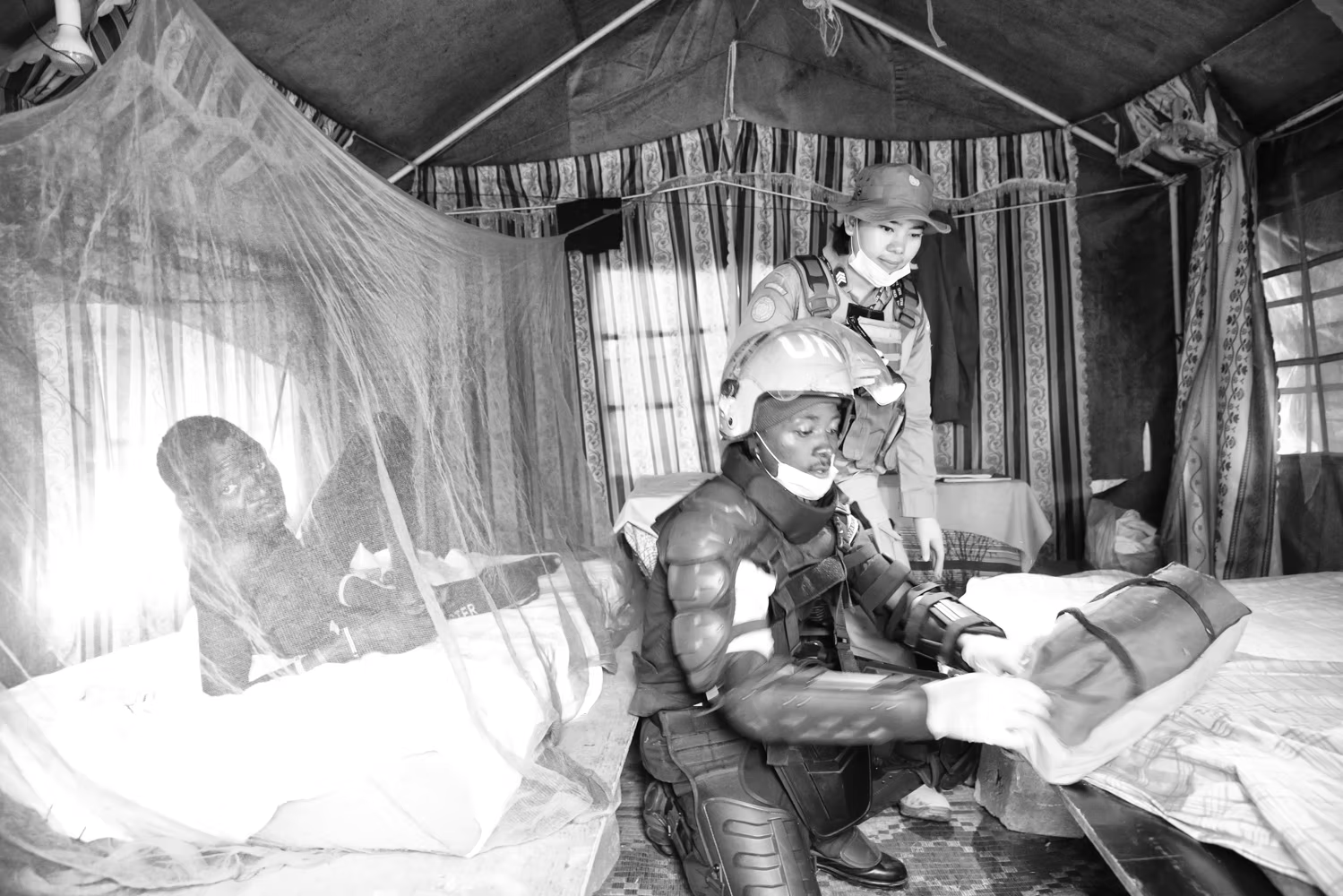

Idomeni on the border of Greece and FYROM was different, here I said goodbye and bid the refugees farewell and safe travels. Things at the border were calm. We were averaging seeing 260 patients a night as refugees got off buses and crossed the border into FYROM. Then the inevitable happened. The border closed last week only occasionally opening to Syrian, Afghans and Iraqi refugees. All other refugees/migrants were refused entry.

A large fence was soon erected on the FYROM border and I witnessed 12 Iranian refugees who sewed their lips in hunger strikes to protest and after several days rioting and looting occurred, people were hungry and cold after days of waiting at the border, and still buses kept arriving with more and more refugees that weren’t able to pass.

Soon, refugees from countries not allowed to pass, in protest, blocked the path for all people wanting to pass, including Syrians. Fighting amongst the refugees began with weapons including batons, knives and even rocks were being used. During one of these days more riot police arrived and we were preparing for an onslaught.

While we were waiting away from the chaos, I received a call from a journalist screaming at me on the phone that a man had been electrocuted on the train tracks and he was burning. By the time the doctor and I got there, it was too late. He had died. A Moroccan man about 20 years of age. I was left to deal with concealing the body from photographers and supporting his grieving and shocked brother.

Suddenly the group of 10 men surrounding us turned into 100 as word got out that the man had died. As I finished zipping up the body bag a group of 8 men picked him up onto their shoulders, then the crowd started chanting. The police had no control of the situation as they were outnumbered. The group stormed off with the body to the border to show everyone and the worldwide media what this situation of closing of the border had done. An accidental death, the man had climbed up on the carriage not realizing he would get electrocuted. The man’s death caused an eruption amongst thousands of refugees and suddenly, tear gas, water cannons and rubber bullets were being sprayed in our direction.

Losing the doctor in the crowd, I climbed up a small hill over the train tracks and headed up through a field. As I made my way towards where our medical van was parked, a man was carried out onto the road from the crowd. He was laid down in front of some police vehicles and as I walked towards him I saw he was frothing at the mouth and nostrils in an altered conscious state.

As I leaned over to check his airway, I saw he was breathing and was affected by the tear gas. I looked up to try and get the team’s attention in the van and saw a man take two steps towards me and swing. I was suddenly hit to the face with a metal pole. There was no reaction. I was stunned. I still had my hands on the patient as I had no time to react. I had severe pain in my jaw and could taste blood.

As I remained kneeling and thought about lying back, I told myself to stay in control and remain kneeling as they might kill me. I started spitting out blood and turned to face the police to show them that I had been hurt.

The man that hit me circled again but refugees started yelling at him. He kept saying ‘police’ but another man yelled out ‘doctor’. He came over raising the pole again and then the look on his face when he realized I was not the police, I will never forget it. He was mortified. He lowered the pole and kept saying ‘Sorry! Sorry!’ Then he came and kissed me on the forehead and held me.

A woman took off her scarf and wiped the blood off my face but by then the tears started rolling and I couldn’t stop crying. A young man patted me on the forehead and kept saying ‘Sorry my sister’. He helped me up and walked with me to the medical van. The police nearby, ironically, did nothing.

There were 8 of them and four fireman sitting in a vehicle. I cried, more for the overwhelming kindness and the response by the refugees. I now have 5 stitches in my mouth and x-rays revealed no fractured jaw but I’m sore and tender. I can’t feel any anger for the man that did this; I understand that there was fighting happening at the time. I’m here for one more month, I agreed to stay and help cover the Christmas holidays as they don’t have staff available.

This experience has been life changing as I have been a part of events that are history in the making and am proud to have been an Australian volunteering over here. I had raised money for medical supplies and medications, campaigning prior to leaving Australia, and saw first hand the difference that these much needed supplies made in a country already crippled in a financial crisis and overwhelmed by this humanitarian crisis.