For all her extensive travels throughout Europe as a young woman, Jackie Kennedy had never been to Greece and had longed to visit the country for a long time.

But her interest was piqued In 1960 when the film Never On Sunday swept the Oscars and captivated the public’s imagination. Ms. Kennedy was enthralled with Melina Mercouri and what she stood for as an artist, and as a Greek.

She even once using Mercouri’s ideas on what it meant to be Greek in backing her argument to historian Arthur Schlesinger that her husband was more a Greek “defying the fates,” than a noble Roman statesman.

It was now the summer of 1961 and “Greek Fever” was at its peak — and the American First Lady had it bad. She planned an “unofficial” trip for June.

Greek Prime Minister Constantine Karamanlis ordered the highest level of security for the First Lady, exceeding that which was provided for Vice President Lyndon Johnson when he visited the year before.

The Prime Minister and his First Lady Amalia Karamanlis were both on hand to greet Ms. Kennedy and her entourage at Athens Airport, where she was greeted with chants of “Jackie! Jackie!” and a group of U.S. Embassy employee wives who assembled in a straight receiving line, greeting her as if she were a queen.

At one point, after exchanging quick welcome pleasantries with the prime minister and his wife, her eye caught a group of young boys dressed as evzones and she broke from her official path and headed to the boys, kneeling to spend several moments talking to them while the entourage waited for the First Lady to finish.

The First Lady chatting with junior evzones who greeted her upon arrival in Athens

The First Lady, her sister Lee Bouvier Radziwll and brother-in-law Stanislaw were hosted in a magnificent villa on Kavouri Bay, south of Athens, owned by Greek shipping magnate Markos Nomikos. Her bedroom on the top floor had a view of the Saronic Gulf.

Almost immediately upon settling, Jackie removed her black hair bow, light blue coat and royal blue dress and put on her bathing suit and headed for an ocean swim.

The next day, June 8, Jackie would begin an island tour aboard the luxurious 123-foot long Northwind, a yacht owned by her host.

On her first stop, the thyme-scented town of Epidavros with its prominent ancient theater on the eastern coast of the Peloponese, she watched a rehearsal of Electra by Sophocles, performed by the Greek National Theater.

Her next stop was the island of Hydra on the morning of June 9. Her experience there, according to her personal memoirs, was the stuff fairytales are made of. The moment she set her foot on the dock from the yacht’s launch, every single church in town began ringing its bells and practically the entire population of two thousand residents rushed towards the cobblestone path to greet her.

She was led down the quaint alleyways by the mayor and all along the way, people were applauding, smiling at, and waving to Jackie. Many threw roses and other fresh flowers at her.

When she learned that local officials had been busily organizing an impromptu festival just to honor and welcome her, she sent word back to the yacht that she was canceling plans for other excursions the remainder of that day, and staying on Hydra.

In the center of town, long wooden tables were set up and local women brought long trays of regional food delicacies freshly-caught fishes, island-raised lamb, cheese pies and other traditional cuisine.

Local tavern owners donated bottles of ouzo, wines and beers. Musicians gathered and began playing traditional Greek music as well as adapting their bouzouki instruments to popular tunes of the era – including the by-now familiar theme of Never on Sunday, which put a huge smile on the First Lady’s face.

Jackie let go and indulged, sampling almost every kind of food that was brought in front of her. In between, she joined hands with townspeople and participated in traditional dancing, raising her arms, clapping her hands, kicking her legs and turning her feet as she followed the steps of each dance move.

“I want to have a home here someday,” she remarked to Greek reporters at one point. “I want to return and bring my children here.”

The next day, she traveled to the island of Delos, legendary birthplace of the Greek god Apollo, where she walked tirelessly amongst the ruins that dotted the island. She took a break to water-ski across the azure blue waters of Delos’ coast headed to the larger island of Mykonos.

Jackie’s legendary arrival at Mykonos port

With a plain red kerchief tied under her neck and a simple sleeveless sundress, she was whisked to the harbor from the yacht which was parked out in the harbor on a speedboat.

She was warmly greeted on the dock by the mayor and dozens of local dignitaries– and a beautiful, large and unusually calm pelican—the icon of the island. The animal immediately captured her curiosity.

“Is he wild?” she curiously asked the Mayor of Mykonos upon her arrival.

“Is he wild?” she asked the mayor. He was, in fact, Mykonos’s most famous resident. His name was Petros. Although politely accepting the mayor’s gift for her daughter of a native costume, and attentive as he explained how the skirt, blouse, scarf and shoes were hand-made and embroidered by local artisans, Jackie remained intrigued by Petros as the bird listened to the story as well. She knelt to gently pet his head, neck and back, asking more about him. Although taken on as the island’s official mascot only seven years earlier, Petros the Pelican was already legendary.

In the aftermath of a violent storm, which churned the Aegean Sea, a fisherman had spotted him lying injured on the island’s Paranga beach and brought him to town where a veterinarian nursed him back to health. The bird was diverted from his natural migration pattern by the storm and Mykonos became his permanent home.

*An interesting future note, twenty five years after this trip to Greece in 1986, a drunk driver hit and killed Petros the Pelican. At the time a publishing editor in New York City, Jackie learned of Petros’ death and immediately began an effort to locate, purchase and donate another pelican for Mykonos, this one named Irini.

Jackie waved away the offer of a car and instead walked with her entourage up the steep incline to the grand island villa of the nation’s only woman newspaper publisher, Helen Vlachos.

Along the way, she poked into shops, chatting with merchants and bought a hand-carved wooden boat for her son for 700 drachmas, or about $25. During her lunch with Vlachos, seated amid flowering fruit trees, Jackie remarked that, “this is the greatest trip in the world. I couldn’t be happier.”

The Greek Prime Minister and his wife were on hand to welcome Jackie back to Athens, when her yacht docked at the mainland on June 11. She hiked to the top of the cape with them to tour the fifth century B.C. Doric temple of Poseidon at Sounion, where hundreds of Greek and other foreign visitors cheered her.

Visiting the site of ancient Cape Sounion with the Temple of Poseidon in the background

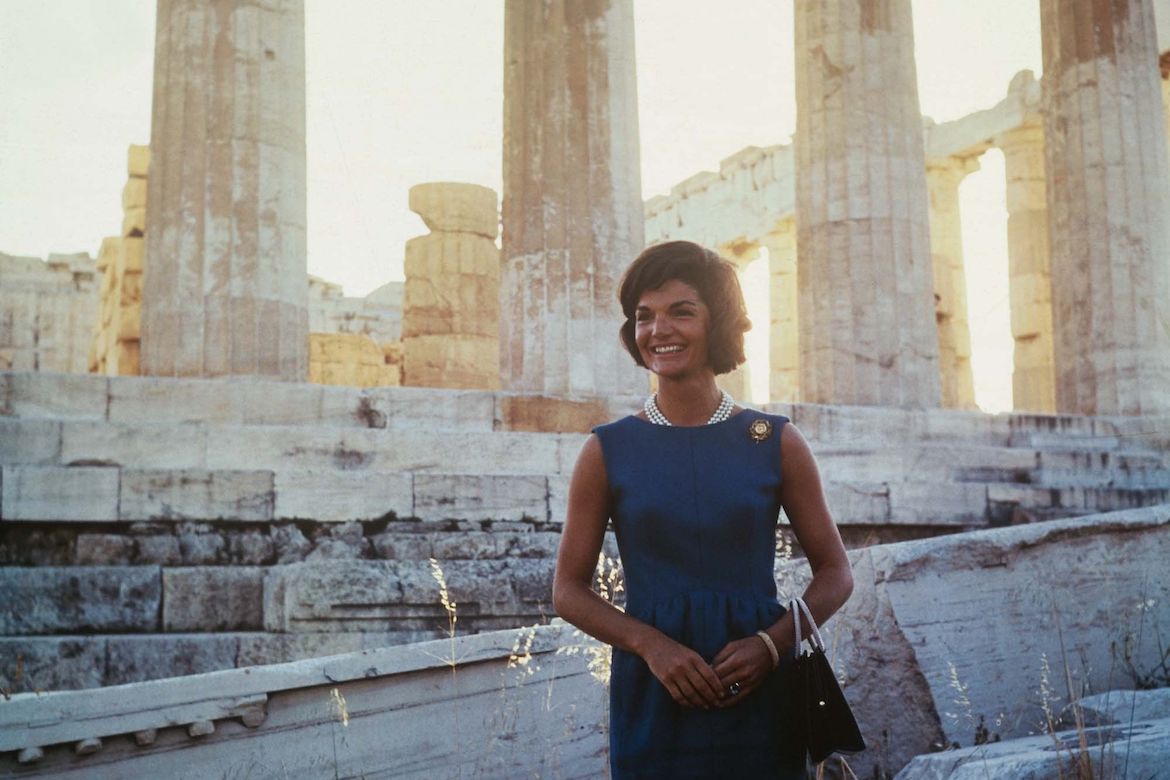

As the sun set, Jackie then went to look at various archeological digs in progress along Cape Sounion. The next day, while touring the nation’s most famous historic sites, the ruins of the Parthenon temple to the goddess Athena, the American First Lady injected herself directly into an international political controversy.

As she was guided through the sites by the Parthenon’s curator, Jackie said she would “like to see the Elgin Marbles returned to Greece,” a reference to the marble sculptures that were removed from the site and taken to England by the Scottish peer Lord Elgin, eventually becoming part of the British Museum’s permanent collection in 1815. Jackie Kennedy’s public voice on the matter came at the beginning of a movement that would soon gain global attention, to return historic artifacts to their original sites from the colonial or invading nations, which had plundered them.

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and First Lady Amalia Karamanlis, to whom Kennedy famously expressed her desire to see the Parthenon Marbles returned to Greece

If her dancing and eating on Hydra, and her affection for Petros on Mykonos had endeared Jackie to the residents of those islands, her unambiguous support of returning the Elgin Marbles to Greece forever won her the affection of the country she would come to make her second home in 1968, when she would marry her second husband Aristotle Onassis.

After a week of relative freedom to be herself, Jackie Kennedy began to transition back to the reality of her public persona, assuming the formal, official demeanor of a First Lady – but not without a defiant, final touch of La Dolce Vita.

On the night of June 13, she was attending a formal dinner hosted in her honor by the Prime Minister.

The next day, her hair once again stiffly coiffed and wearing a light orange dress suit, she ascended into the hills about fifteen miles from Athens for a formal luncheon with King Paul, Queen Frederika, Princess Sophia, Princess Irene and Prince Constantine at their Tatoi summer palace.

Poodle petting with the Greek royals

She then joined them on the manicured lawn to pose for reporters and photographers — and pet the Queen’s three grey poodles. There was also a formal exchange of state gifts. She was given a multi-colored Greek carpet and in return, presented a velvet-lined mahogany case with a portable American compass, made in Maine of sterling silver and gold plate. Her forced smile, however, made her discomfort obvious.

Catching this signal, the 21-year old jet-set heir to the throne, a 1960 Olympic gold medalist in sailing, had a solution. After lunch and breaking from the official schedule that had been planned for the day, Prince Constantine invited the First Lady to hop into his blue convertible sports car and join him to see his boat.

Jackie and Prince Constantine en route to see his sailing boat at the port of Piraeus

Jackie impulsively took the dare, jumping in to speed away with Constantine around sharp curves down to the Port of Piraeus. It was a last gasp of a semblance of freedom that she had already experienced on this exhilarating — and liberating — trip to the Greek Isles.

Jackie’s 1961 tour of Greece failed to generate the level of global media coverage that her trips to Paris, Vienna and London had in the preceding months for a number of reasons. No longer touring with the President, political news outlets considered a First Lady’s travels unimportant. Her mixing it up with the “peasantry” lacked the glamour that the fashion glossies wanted, like when she hobnobbed with celebrities in Paris and London.

Touring a series of islands was also a tougher narrative to compact, especially since the trip was billed as unofficial. Nonetheless, Jackie Kennedy’s trip to Greece was an important component in her agenda to promote American goodwill in less accessible points around the world. From her arrival in the country, her appearance, words and deeds gave those who met her and those who simply read about her, an entirely different Jackie than the formal and official one they expected from a U.S. First Lady.

Jackie at the Parthenon

Her hair blew freely in the wind, her legs bare of stockings, wearing sandals, cotton head kerchiefs and the sunglasses that would eventually supersede the pillbox as her trademark. Beloved to all who met her, Jackie Kennedy showed reverence and respect for her host nation’s culture and history. Her respect for Greeks of all classes won her the nation’s respect and affection.

From dancing to Greek music to supporting the return of Greek treasures to displaying fondness for a beloved Greek animal mascot, the American First Lady’s genuine respect for the native culture of the Greek people was also her campaign to improve the foreign perception of the U.S.