Like a bolt out of the blue, tanks surrounded the Greek parliament on April 21, 1967 as a cabal of junior officers launched a military coup to thwart impending elections. Arresting more than 8,000 citizens, the coup installed the oppressive military junta that would rule Greece for the next seven and a half years.

In Washington, news of the coup posed a thorny challenge to the government of Lyndon Johnson, already under political siege for its war in Vietnam. Unlike other military coups during the Cold War, the Greek junta had not seized power in some distant “Third World” country. Instead, Greece was a NATO ally on the frontier of the East-West division of Europe.

Two decades earlier, the United States, under the 1947 Truman Doctrine, had intervened in the Greek civil war in order to defeat the communist Left, rescue the country’s flawed but functioning crowned democracy, and keep Greece from slipping into the Soviet orbit.

A catalyst in forging bipartisan support for America’s postwar rivalry with the Soviet Union, the Greek intervention was celebrated by Democrats and Republicans alike as a Cold War victory for democracy. Now a dictatorship gripped Greece.

Months before the 1967 putsch, US intelligence reported that King Constantine had ordered the army chief of staff to prepare contingency plans for a coup to avert a return to power of the liberal Center Union, which had challenged his interventions in parliament. But the King also appealed to Washington for a covert CIA program to rig the elections against the Center Union should they go forward.

Six weeks before the military coup, the National Security Council’s 303 Committee, chaired by Johnson’s national security adviser Walt Rostow, met to consider the King’s appeal.

Writing in the Washington Post a decade later, Jack Maury, CIA Station Chief in Athens in 1967, recounts that the interagency committee “ultimately disapproved” the covert election-rigging scheme. But he also recalled that, “as one very high administration official remarked: ‘Maybe we should let the Greeks try a military dictatorship; nothing else seems to work over there’”. (1)

As it happened, the colonels who executed the coup caught the King, Greece’s top brass and many US officials by surprise. “It was the right coup, but the wrong guys!”, wrote embassy defense attaché O.K. Marshal to the State Department. The “wrong guys” were the junior officers who, recruited by the King’s generals to prepare the coup plan, had seized the initiative themselves, taking the King, who grimly endorsed their actions, political hostage.

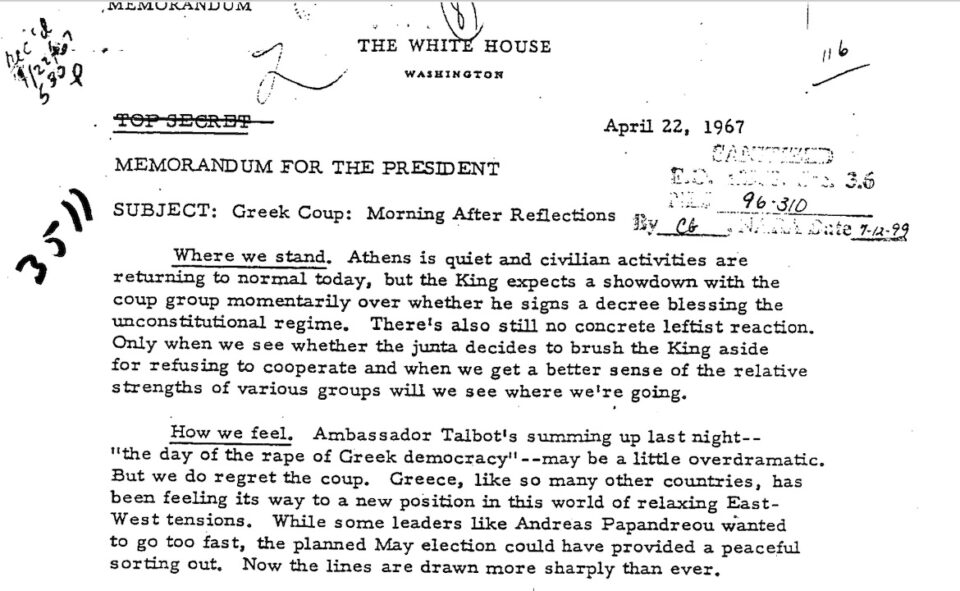

The day following the coup, Rostow sent morning-after reflections to President Johnson placing Greek developments in a broader context. “We do regret the coup,” he wrote. “Greece, like so many countries, has been feeling its way to a new position in this world of relaxing East-West tensions. While some leaders like Andreas Papandreou wanted to go too fast, the planned May election could have provided a peaceful sorting out. Now the lines are drawn more sharply than ever.” (2)

Click here to read the full April 22, 1967 memorandum for President Johnson

In evoking relaxing East-West tensions, Rostow was referring to the US-Soviet détente in Europe that President Kennedy had inaugurated in the aftermath of the 1963 Cuban missile crisis. In the early Sixties, a liberal awakening began gaining momentum in Greece. In 1964, the Center Union won a sweeping electoral victory on promises of greater democracy and national independence, bringing a decade of stultifying conservative rule to an end.

Prime Minister George Papandreou, with Andreas, his popular son, at his side, soon came into conflict with the King over control of the army. But his government also had angered the US by scotching an American plan to divide recently decolonized Cyprus between Greece and Turkey.

In US policy circles, Cold War hawks grew fearful of losing Greece, home to four US bases, as a strategic military asset. In 1965, the King forced George Papandreou to resign, triggering an intractable political crisis that opened the way to the 1967 putsch.

While Rostow regretted the coup verbally, his actions demonstrated on which side of the sharply drawn lines he stood. Rather than issue a statement condemning the coup, the Administration remained silent.

“The new leaders are still trying to flesh out their government and broaden its membership as much as possible,” Rostow explained to Johnson. “With the situation still in flux, we shouldn’t do anything to tip the balance publicly.” (3)

A week later, the State Department finally released a press statement expressing regret at the suspension of democratic processes. But the statement also welcomed the new regime’s declaration of continued devotion to NATO, as well as the King’s call for a quick return to constitutional rule.

Meanwhile the US imposed an arm embargo that the Pentagon would covertly evade. As an NSC official would explain to Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon, Pentagon evasion of the embargo had enabled the US “to straddle the fence between continuing basic supplies to a NATO partner while maintaining a semblance of disapproval for domestic political purposes.” (4)

The King’s call for a quick return to constitutional rule was, in fact, spurious. Hostile to the entire political world—Left, Right and Center—the reactionary junta had no intentions of relinquishing power. Seven months after the coup, In December 1967, the King launched a counter-coup. Its failure saw him flee to Rome, adding royalists to the fractious, ideologically diverse contingent of anti-junta Greeks living in Western exile.

Soon after, the junta declared a Christmas amnesty, releasing a number of political prisoners. These included Andreas Papandreou, whose months of solitary confinement had made him a cause célèbre in the West. A sense of euphoria briefly swept the country in the belief that the regime was preparing a transition back to civilian rule. But hopes were soon dashed.

Of the 3,000 or so political prisoners expected to benefit, fewer than 300 were finally released, with many of them simply transferred from their prison cells to island exile. Instead, the junta’s wily dictator, George Papadopoulos, in moves carefully choreographed with Washington, moved to consolidate power.

Events ahead of the King’s failed counter-coup had prepared the way. Six weeks after the April 1967 coup, the outbreak of the Six-Day War in the Middle East had intensified the Pentagon’s pressure on President Johnson to normalize relations with the Greek junta. At the same time, Papadopoulos earned kudos from US foreign policymakers in November 1967 for his handling of a crisis in Cyprus that threatened to bring two NATO allies, Greece and Turkey, into military conflict.

Johnson sent Cyrus Vance to the region as a special envoy. Working collaboratively with Vance, Papadopoulos had defused the crisis by withdrawing a Greek military division from the island. In the aftermath, Vance wrote a glowing report on Papadopoulos whose handing of the crisis “demonstrated not only loyalty to the Western alliance, but also the capacity to comprehend a complex problem of statecraft [my italics].” (5)

In fact, by withdrawing the Greek division, Papadopoulos had weakened Cypriot defenses against the repeated threat of a Turkish invasion that would finally take place with disastrous consequences in 1974.

After the King’s failed counter-coup in December 1967, the Greek colonels no longer faced an internal threat from the royalist generals, leaving junta leader Papadopoulos securely in power. Conditions were now ripened for normalization of US-Greek relations.

Brokering the enterprise politically was Greek-American businessman Tom Pappas, who would later gain notoriety as the man President Richard Nixon would turn to in order to secure hush money for the Watergate burglars.

Later also a junta back-channel to Nixon, Pappas delivered a personal letter from Papadopoulos to President Johnson in January 1968. The letter reassured the Johnson of the junta’s intentions to hold free elections, “if this were practically possible and psychologically advisable.”

Four days later, Johnson sent a reply informing Papadopoulos that, while not making “a formal announcement”, the Administration had “decided to move in the near future to a working relationship with the regime in Athens.” (6)

The Johnson-Papadopoulos exchange was kept secret, both in Washington and Athens. But not long after, the U.S. Ambassador to Greece, Philips Talbot, welcomed Prime Minister Papadopoulos aboard the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt aircraft carrier for lunch and an underwater operations demonstration.

Treated to photographs of the event in Athens’ government-supervised press, the Greek public got the message.

When Richard Nixon took office in January 1969, Greece’s political nightmare would go from bad to worse. Dropping all “semblance of disapproval”, Nixon moved to fully embrace the military regime, which for most of its tenure ruled through martial law.

In the end, the Greek dictatorship junta collapsed in 1974 in the wake of the bloody Turkish invasion of Cyprus that the junta had itself provoked. By an irony of history, that collapse came in the same weeks that Nixon was forced out of the White House by the Watergate scandal.

References

1. “The Greek Coup: A Case of CIA Intervention? No, Says Our Man in Athens”, John M. Maury, Washington Post, May 1, 1977.

2. Walt Rostow, Memorandum for the President, “Greek Coup: Morning After Reflections”, April 22, 1967, Top Secret, Declassified Document Reference System.

3. Walt Rostow, Memorandum for the President, “Our Posture on the Greek Coup”, April 22, 1967, Secret, Declassified Document Reference System.

4. Foreign Relations of the United States, XXIX: Eastern Europe; Eastern Mediterranean, 1969–1972, document 257, “Military Supply Policy Towards Greece,” October 7, 1969.

5. National Security File, Country File, Box 124, “Vance Mission Final Report, Vol. 1.” Document #15. LBJ Presidential Library.

6. Foreign Relations of the United States, XVI: 1964–68: Cyprus, Greece, Turkey, document 352, January 6, 1968.

About the author

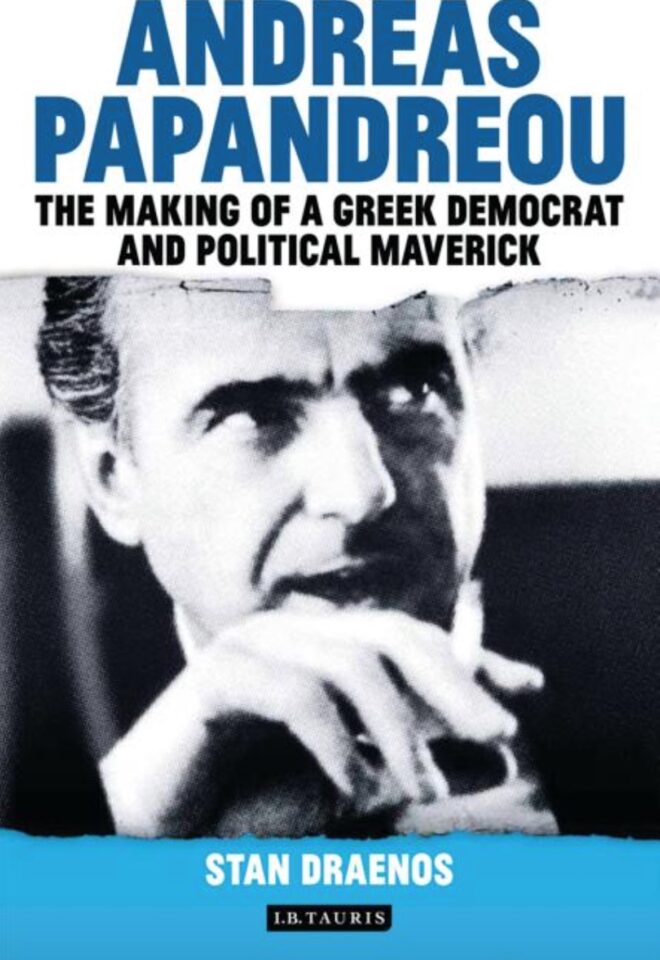

Stan Draenos is a Greek American living in Athens. He is a historian, political analyst and the author of a biography about the early life of former Greek Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou. His book is called “Andreas Papandreou: The Making of a Greek Democrat and Political Maverick” and is available for purchase via Amazon or via The Pappas Post Bookshop.

NOTE: By purchasing the book through our bookshop instead of Amazon you can directly support our efforts as we receive a larger portion of the profits.