As I travel around presenting my new book The Greeks and the Making of Modern Egypt published by the American University in Cairo Press, speaking to audiences in Boston, Ottawa, Cairo, Athens — and soon in Philadelphia and Atlanta — I have come to reflect on the parallels between the experiences of the Greeks in Egypt and the Greeks in the United States.

The Greeks in Egypt were the largest Greek diaspora community until the beginning of mass emigration from Greece to the United States in the early twentieth century.

By the 1920s the numbers of the Greeks in Egypt, just over 100,000, were only second to that of the number of Greeks in the United States, which hovered around 350,000. And at the time, Alexandria with about 40,000 had a larger number of Greeks than Chicago or New York. Eventually of course, due to Egypt’s nationalist measures, the numbers of Greeks in Egypt would decline precipitously after WWII.

But the parallels between the two most important diaspora communities in Greece’s modern history go far beyond their numbers.

The Greeks were in Egypt in the nineteenth century, initially because they were invited by the country’s ruler Muhammad Ali to help modernize the country. Several Greek merchant houses played an important role of the export of Egyptian cotton, which was the mainstay of Egypt’s economy. The largest of those merchant houses extended their operations across the Atlantic Ocean to deal in American cotton as well, this was the case of the Rodocanachis or in the case of large merchant families such as the Benakis, one branch of the family settled in Egypt, the other in America.

Nikolaos Marinos Benakis was based in New Orleans where he also served as Greece’s Consul. He was the prime mover behind the establishment of the Holy Trinity Church in New Orleans, the oldest Greek Orthodox church in North America.

Owning their business was another parallel between the Greeks in Egypt and the Greeks in the United States. Everyone remarked on the ubiquitous presence even in the remotest of all towns of the small Greek-owned grocery, known as the bakkal, using the Turkish word which has also become the Greek “bakalis.”

The reliable companion for nineteenth century travelers, Baedeker’s guide to Egypt (published in 1898), reassured those wanting to venture south to the ancient Egyptian sites that “in most towns the Greek bakkal keeper will provide a small sleeping room.” Surely, if the famous Baedeker guides had lasted and had produced an American edition, they would have reassured weary travelers that they could count on having a meal at a Greek-owned diner in any American town — big or small.

The Greeks Bring the Egyptian Cigarette to America

The Greeks also dominated cigarette manufacturing in Egypt, which was done by hand until the introduction of machines in the early twentieth century. The Greek cigarette manufacturers, who had been originally based in the Ottoman Empire, specialized in blends that relied on tobacco leaf grown in what are present-day Greece, Syria and Turkey and they produced what became known worldwide as the luxury “Egyptian cigarette.”

The Egyptian cigarette held its own globally until the American companies peddling the Virginia blends displaced it by WWII. But in the meantime, several Greek manufacturers opened shop in North America, because high tariffs made exporting to the United States unprofitable.

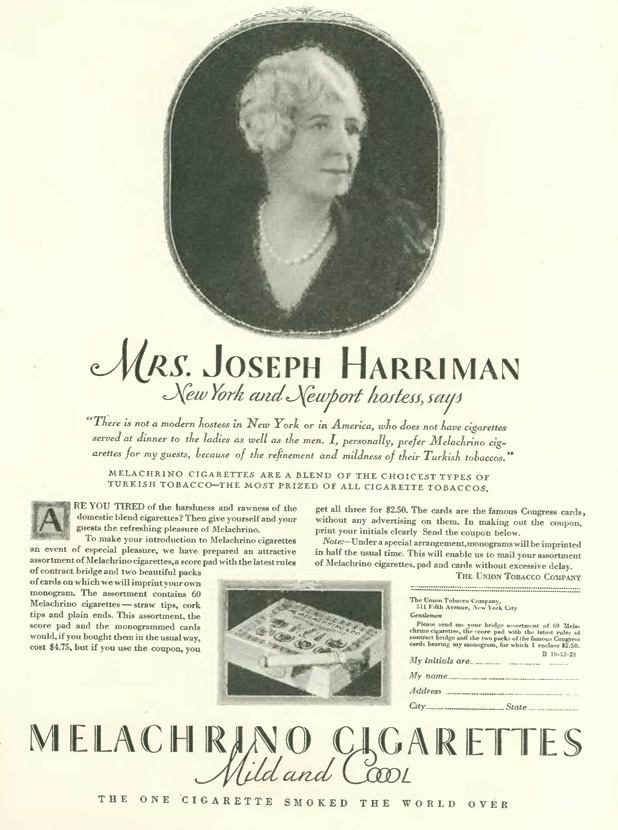

These manufacturers included Miltiades Melachrino, who established a cigarette manufacturing branch in New York.

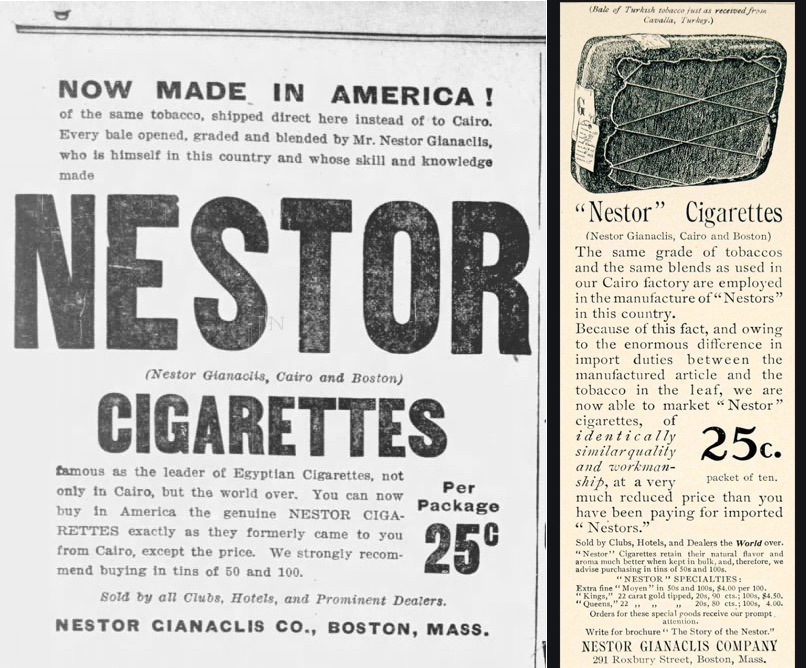

Nestor Gianaclis — who to this day has a neighborhood named after him in Alexandria — established his own cigarette manufacturing branch in Boston.

Gianaclis’ business opened in a warehouse at 291 Roxbury St, and the first advertisement for his cigarettes appeared in the Boston Globe on January 1, 1906.

Melachrino’s marketing strategy was to solicit endorsement of his cigarettes by well-known personalities including members of several European royal families. In the United States he sought and received the endorsement of Augusta Barney, the wife of banker Joseph Wright Harriman.

The Balkan Wars of 1912-13 disrupted tobacco leaf exports from the Ottoman Empire and endangered both those firms. The Melachrino company bought out Gianaclis, whose owner Nestor continued the business in Egypt and prepared to launch another successful venture, growing wine on the banks of the Nile. But Miltiades Melachrino left the running of the business to his associates and returned to Cairo, where with the fortune he had amassed he financed the building of a Greek school in the suburb of Heliopolis.

The Post-Revolution Greek Exodus from Egypt to America

In the second half of the twentieth century, a small wave of Greeks left Egypt for Canada and the United States. In Egypt, the nationalist revolution of 1952 accelerated measures to “Egyptianize” the economy that were already underway. This restricted the privileges that foreigners enjoyed — which had already eroded significantly.

And the future looked dismal, all the more so after the Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser expelled British and French residents in 1956 after their governments opposed his nationalization of the Suez Canal. The final blow for most Greeks would come when Nasser enacted a wide range of nationalization of privately-owned businesses in the 1960s.

By 1967, the once 100,000-strong vibrant Greek community in Egypt was reduced to a paltry 17,000. That number would get smaller and smaller until only about three to four thousand Greeks remained in Egypt. The exodus that had begun in the 1950s was directed towards Greece, although the Greek government was able to successfully persuade many to go to Australia — which was trying to attract migrants who would work in the manufacturing sector. But the choice destination for English speakers and the well-educated was the United States.

The prestigious institutions in Egypt — which included the Greek Abeteios high school in Cairo, the Averoff high school and the British Victoria College in Alexandria — offered a first-class high school education that enabled many to go on to study in Britain, Canada and the United States.

Canada and the United States in particular proved fertile ground for the careers of Greeks in Egypt who were blessed with a cosmopolitan outlook compatible with North American multiethnic society — especially in jobs that required international expertise.

The numbers of Greeks from Egypt coming to the United States were large enough to do what else but to create a “topiko somateio,” the very popular form of Greek American organization whose members come from the same island or region. In this case they all came from the same country, Egypt.

They formed the Association of Hellenes from Egypt in America (AHEA) in November 1957 and remained very active for more than three decades.

Slowly, of course, the generation of Greeks that grew up in Egypt and came to the United States grew old and some are not with us anymore, but their obituaries record the ways their cosmopolitan background enabled them to achieve professional success and contribute to their second adopted country.

Among those Greeks was the Alexandria-born Platon Coutsoukis, who received his doctorate in sociology from Boston College with a thesis focused on “corporate citizenship.” While at the university’s social welfare institute he co-authored a book entitled Gospels of Wealth: How the Rich Portray their Lives. The title echoes of that of a well-known book by Andrew Carnegie.

Knowledge of several languages and a worldly outlook propelled the professional careers of several Greeks from Egypt.

Nicholas S. Gounaropoulos (1927-2001), who was born in Cairo and died in New York City, served the United Nations for more than 30 years in Europe, the Far East and Africa.

The life of John K. Kalliarekos, who was born in Port Said (1932-2003), further illustrates the ease with which Greeks in Egypt adapted to America’s multiethnic society. Kalliarekos, who came to the United States in 1982, became vice president of export sales for the Hercules Tire and Rubber Co. in Ohio.

At a young age Kalliarekos took the reins of his family business in Egypt, one of the largest providers of supplies to the marine traffic passing through the Suez Canal. During the late 1960s, as the Greeks were being forced out of Egypt, Kalliarekos emigrated to Athens, Greece, from where he represented several American companies in the markets of Southern Europe, Africa and the Middle East — and then moved to the United States. He spoke Arabic, French, Greek and English.

Naturally for a group of Greeks that came from a diaspora community that valued education for boys and girls, several Greek Egyptian women had successful careers in the United States. Maria Vernicos Carras Rolfe (1913-1983) was one of them.

Carras grew up in London and worked in international business, investing and philanthropy. She emigrated to the United States in 1959 and the following year married her second husband, international economist Sidney E. Rolfe (1921-1976). Upon his death, Maria Rolfe determined to continue his legacy in the field of economics by working to include more women in the higher echelons of that and related fields. In 1978, she founded The Women’s Economic Round Table, Inc. (WERT), an educational and networking forum in the fields of national and global economics, finance and business.

Alec Courtelis

But peraps the most colorful of all Greek Egyptian lives in the United States was that of Alec Courtelis (1927-1995). After his death, the Miami Herald reported on December 29, 1995 that former US President George H.W. Bush saluted his friend saying “Who says there are no heroes any more? Just look at the life and legacy of Alec Courtelis.”

Tough in business but generous in spirit, Courtelis gave time, advice and money for people and causes in which he believed, the newspaper explained. An immigrant and self-made businessman, Courtelis rejoiced in saying that nothing is impossible in America and viewed his life as an adventure.

Born in Alexandria, Egypt, Courtelis emigrated to Miami in 1948. At the University of Miami, he earned a degree in engineering and met his wife, Louise Hufstader. In 1961, he founded Courtelis Company, which built The Falls shopping center in Southwest Dade and developed commercial and residential sites throughout Florida. Real estate development was something the Greeks had pursued in Egypt in earlier times.

As he succeeded in business, Courtelis wanted to give something back to the country he adopted.

He became active in political fund-raising and was appointed to the Florida Board of Regents in 1988 by Republican Gov. Bob Martinez. A staunch Republican, he became a top party fundraiser, “almost a hobby,” he called it.

Courtelis helped raise money for President Ronald Reagan’s campaigns and, in 1988 and 1992, served as national finance cochairman for the Bush-Quayle campaign. But repeatedly, he left partisan politics behind for the sake of state schools.

When newly elected Gov. Lawton Chiles, a Democrat, proposed a tax increase in 1992, Courtelis campaigned for it, saying the state education system needed the money. Courtelis eventually served as chairman of the Board of Regents, which runs Florida’s state universities, and also joined the board of trustees of the University of Miami and became a school benefactor.

As the Miami Herald put it, “In Gainesville, Alec and Louise Courtelis achieved the status of patron saints of the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine. Horse-breeding enthusiasts, they are credited with saving the college after a string of problems in the late 1980s, helping bring in more than $30 million for the school since 1988.”

Throughout South Florida, business people and political leaders tell stories about his toughness of mind. “He was a fighter and a great inspiration to the whole Bush family,” HW Bush told the Miami Herald.

Yet above all, “it was in his fight against cancer,” Bush said, through which Courtelis showed “what real courage is about.”

In early 1994, Courtelis was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. But he rejected the three-month prognosis doctors gave him to live, refusing to accept what he considered a death sentence approach to medicine.

Back in Miami at UM’s Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, Dr. Pasquale Benedetto encouraged his optimism and started Courtelis on a vigorous, experimental course of chemotherapy.

But Courtelis didn’t stop at conventional therapy. With the help of Teri Amar, a psychotherapist, he learned to visualize his body fighting off the cancer. He concentrated on the good things in life, ate healthy foods and exercised. He turned to the Greek Orthodox Church, in which he was raised. Within months, signs of cancer disappeared.

Doctors stopped short of calling it a miracle, but said his positive attitude and determination played a role in beating back what is usually a fast and lethal cancer. When friends organized a tribute dinner early in early 1994, Courtelis turned it into a fundraiser for a center to make the mind-body approach available to all cancer patients.

The Courtelis Center for Research and Treatment in Psychosocial Oncology opened in September, with more than $1 million raised through Courtelis’ efforts. Later on, the disease reappeared, this time with a lethal effect. But Courtelis and his wife had time to go to London to attend the wedding of Pavlos, the son of former King Constantine of Greece to Marie Chantal Miller, and continue on to Greece for one final island cruise.

Courtelis is only one of the many Greek Egyptians who came to the United States, did well and then did good for their community. They were born in a land where the Greeks had prospered for generations, but they could not stay on there because Egyptian society had chosen the path of nationalism — making cosmopolitanism and multinationalism a thing of the past.

But those Greeks moved the United States, another multiethnic society that welcomed foreigners as Egypt had done in the past. And there they flourished — as their parents and grandparents had back in Egypt.

About the author

Born in Athens, Greece, Alexander Kitroeff is a professor of history at Haverford College nearby Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His courses focus on the 20th-21st century cultural and social history of Europe and the Mediterranean region, with an emphasis on national and ethnic identities. Kitroeff’s research and publishing focuses on nationalism and ethnicity in modern Greece and its diaspora, and its manifestations across a broad spectrum, from politics to sports. His latest book publication is The Greeks and the Making of Modern Egypt, available for purchase below.

Is The Pappas Post worth $5 a month for all of the content you read? On any given month, we publish dozens of articles that educate, inform, entertain, inspire and enrich thousands who read The Pappas Post. I’m asking those who frequent the site to chip in and help keep the quality of our content high — and free. Click here and start your monthly or annual support today. If you choose to pay (a) $5/month or more or (b) $50/year or more then you will be able to browse our site completely ad-free!

Click here if you would like to subscribe to The Pappas Post Weekly News Update